Lifecycle Quality Best Practice Guidelines

Do you prefer the guidelines as a pdf file?

Download PDFAre you interested in downloading a specific chapter?

Search the reports?

SearchFundamentals of Lifecycle Project Management

Effective Lifecycle Project Management (LPM) ensures that all the necessary actions throughout the development, EPC, O&M, and decommissioning/disposal phases are performed. Therefore, LPM has two different focuses: on the one hand, it has to ensure the timely and cost-effective progress of the project through each of the lifecycle phases; on the other hand, it has to ensure that this progress is not impeded by avoidable problems that could affect the profitability of the project.

While there are other definitions for risk and risk management, in these guidelines we see Risk Management (RM) as the overarching management system which ensures that project progress, throughout its lifecycle, is timely and cost-effective, with a reasonable trade-off between risk and cost. To achieve this, RM includes the following areas:

- Risk Analysis

- Health, Safety, Security & Environment (HSSE)

- Due Diligence

- Quality Management

The four areas can each be divided into four sub-areas. These will be explained below.

4.1. Risk Analysis

RM starts with the Risk Analysis (RA), for which we define the following steps:

- Risk Identification (RI)

- Risk Assessment (RAss)

- Risk Prevention & Mitigation (RP)

- Risk Plan Communication & Implementation (RC)

a) Risk Identification

RI is the beginning of RM. As a minimum, it is important to identify and define all major risks with a significant chance of occurrence. If this does not happen or happens too late, the whole project could be jeopardised.

b) Risk Assessment

Once a risk is identified, an assessment must take place to determine how likely it is to occur, what the impact would be, and estimate the costs of eliminating or reducing the risk.

c) Risk Prevention & Mitigation

Once the RAss has been conducted a decision must be made on the best way to prevent (by establishing barriers) or mitigate the risk and/or its consequences.

d) Risk Plan Communication & Implementation

Once a decision has been made on how to prevent or mitigate the risk, a plan on how to do so must be communicated.

4.2. Health, Safety, Security and Environment (HSSE)

HSSE are priorities throughout an asset’s lifecycle. There are legal requirements in most countries, and internationally accepted standards, such as the IFC Performance Standards and the Equator Principles, to ensure that solar projects do not negatively impact the environment and guarantee a healthy and safe workplace. Furthermore, international financial institutions also use HSSE, and social requirements when assessing projects. Security is often a requirement in insurance policies, otherwise claims can be void.

Good HSSE coordination is fundamental to achieving all HSSE objectives, which can be summarised as follows:

- Establish an HSSE culture within the organisation and the relevant project team

- Establish, implement, and maintain an effective integrated HSSE management system

- Ensure compliance with applicable health, safety, and environmental legislation, codes, and standards and, whenever possible, with higher standards and best practices

- Ensure surveillance of the project site, especially of high-value products, as well as components which are difficult to replace quickly

- Ensure that intrinsically safe design is achieved by monitoring progress and preparation of results and systematically reviewing the design process, if necessary

- Manage risks in the design, procurement, construction, installation, commissioning, operation, and maintenance activities

- Ensure appropriate levels of skills for all staff engaged in carrying out critical HSSE activities and provide training where necessary

- Check for any potential HSSE impacts in the project area and ensure that these are minimised

- Make sure that the site surveillance is in line with the insurance requirements

- Ensure that a complete inventory of all waste and discharges is maintained and that all waste is disposed of in an environmentally acceptable way, in compliance with the relevant regulations

- Review lessons learned, performance and any opportunities to continuously improve, to update safe design

For this purpose, it is important that Asset Owner, the EPC, and other service providers meet to align on procedures to follow to avoid risks, especially when different service providers are working on the site simultaneously.

4.3. Due Diligence

Over the lifetime of a project, the asset, and its operating company – typically a special purpose vehicle (SPV) – move through a number of defined stages.

These stages are typically marked by changes in contractual liability and obligation, and the transitions or ‘stage-gates’ between phases are usually accompanied by contractual documentation. This could be in the form of a new contract starting with a different service provider, or third-party certification, with supporting documents, as defined in an ongoing contract.

A very important step of each due diligence assessment is the collection of the relevant documentation. An advisor should have comprehensive documentation check lists and conduct a “gap analysis” in the data-room. Within this context, the role of the Asset Manager (AM) is also very important as they can ensure that a structured data-room is properly built at all stages of a project.

The Due Diligence (DD) process can be divides into four sub-areas:

- Legal DD

- Technical DD

- Financial DD

- Political DD

Financial DD consists of the Insurance DD, Accounting DD, and Taxation DD.

TABLE 1 - DUE DILIGENCE THROUGH THE STAGES OF A PROJECT'S LIFECYCLE

| TYPE OF DUE DILIGENCE | PERTINENT PHASE | MAIN ASPECTS ANALYSED | NOTES |

| a) Legal DD (consisting of Legal, Environmental, and Compliance DD) | |||

| Legal DD | Development and operation | Development: i. Respect of the relevant constraints ii. Respect of the key legal requirements within authorisation processes Operation: iii. Corporate aspects iv. Legal terms of the key contracts v. Correctness of the authorisation process | |

| Environmental DD | Development, construction, operation, and decommissioning | Verification of the compliance with environmental regulation and safeguarding against environmental accidents such as soil and/or groundwater contamination. | |

| Compliance/reputational DD | Development, procurement, construction, and operation | Verification of the reliability, honesty, and legal compliance of the relevant counterparties. This should include technical, financial, legal, and social dimensions. | There is a serious risk of reputational damage linked to a lack of supply chain transparency. For more information on building sustainable and transparent supply chains, please refer to SolarPower Europe’s Sustainability Best Practices Benchmark. In addition, SolarPower Europe is currently (as of December 2021) developing a supply chain monitoring programme that will further this effort. |

| b) Technical DD | |||

| Technical DD | Development, construction, operation, and decommissioning | Development: i. Yield forecasts ii. Correctness of the layout of the site iii. Respect of site constraints iv. Land /rooftop rights v. Verification of grid connection solutions vi. Key terms of PPAs vii. Quality assessment of key components viii. Assessment of the EPC service providers’ creditworthiness. Construction: ix. Installation quality x. Compliance of as-built design with the approved layout Operation: xi. Production forecasts based on historical data xii. Warranty management xiii. Quality of components xiv. Compliance with key regulatory requirements | A technical advisor or “Owner’s engineer” should be involved during the construction phase. |

| c) Financial DD (consisting of Insurance, Accounting, and Tax DD) | |||

| Insurance DD | Construction and operation | i. Extent of coverage of risks insured ii. Adequate levels of insurance iii. Adequate deductibles | The insurance due diligence should cover both the erection policies, civil responsibility, Directors’ & Officers’ liability and “all risks” during operation. |

| Accounting DD | Operation | i. Verification of the credits and debits in the balance sheet (to quantify the working capital) ii. Verification of operating costs and key occupational assumptions iii. Verification of Profit & Loss and Cash Flow Statement to facilitate onboarding during operations | When a locked box mechanism is applied, due diligence processes should also include the verification of permitted leakages. |

| Tax DD | Operation | i. Verification of the timely and correct submission of tax returns ii. Verification of the effective entitlement to tax benefits requested (if any) iii. Verification of the correct management of VAT credits | |

| d) Political DD | |||

| Political DD | Development, Construction | i. Change of political support for (ground-mount) solar systems ii. Risk of retroactive changes in support schemes iii. Instability of government |

Challenges and opportunities in due diligence processes

An effective due diligence process requires a structured methodology to assess key elements of risks and communicate the related outcomes to decision-makers, in a timely manner. This can result in changes to the structure of a project or the way that investments are monitored.

Relying on a weak methodology, unqualified or inexperienced assessors, or a poorly defined project plan to conduct due diligence, results in a cumbersome and ineffective process that does not produce the key information needed for effective decision-making.

There are numerous challenges in the due diligence process:

- The scope of work may not be well-defined, leaving key questions unanswered

- Information requested may be poorly communicated, leading to more time spent gathering new or different data

- Transaction responsibilities and timelines may not be well-understood; critical matters uncovered during due diligence may not be communicated to the appropriate counterparty

At the same time, there are many benefits to conducting effective due diligence as it can help stakeholders:

- Objectively understand the assets and their underlying historical performance, including deviations from historical and recent trends

- Identify key risks faced by the lender/investors and establish a communication framework to address these risks, including potential mitigation efforts. This could also result in deal-structuring alternatives such as pricing considerations, collateral requirements, or enhancements to required periodic reporting

- Develop an understanding of critical policies and procedures used to prepare information used for decision-making and identify potential areas of information weakness

Market confidence relies on and will improve with more effective and frequent due diligence. Increasing the cost-competitiveness of solar PV in the future will rely heavily on quality due diligence services can help avoid asset underperformance, or non-performance.

4.4. Quality Management

Quality – if not set by clear criteria and measurements – is a perceptual, conditional, and somewhat subjective attribute and may be understood differently by different people. In general, it can be defined as a commitment to customers in the market or as fitness for intended use, in other words, how well the product performs its intended function. Quality also encompasses the reduction of harm that a product may cause to the environment or human society.

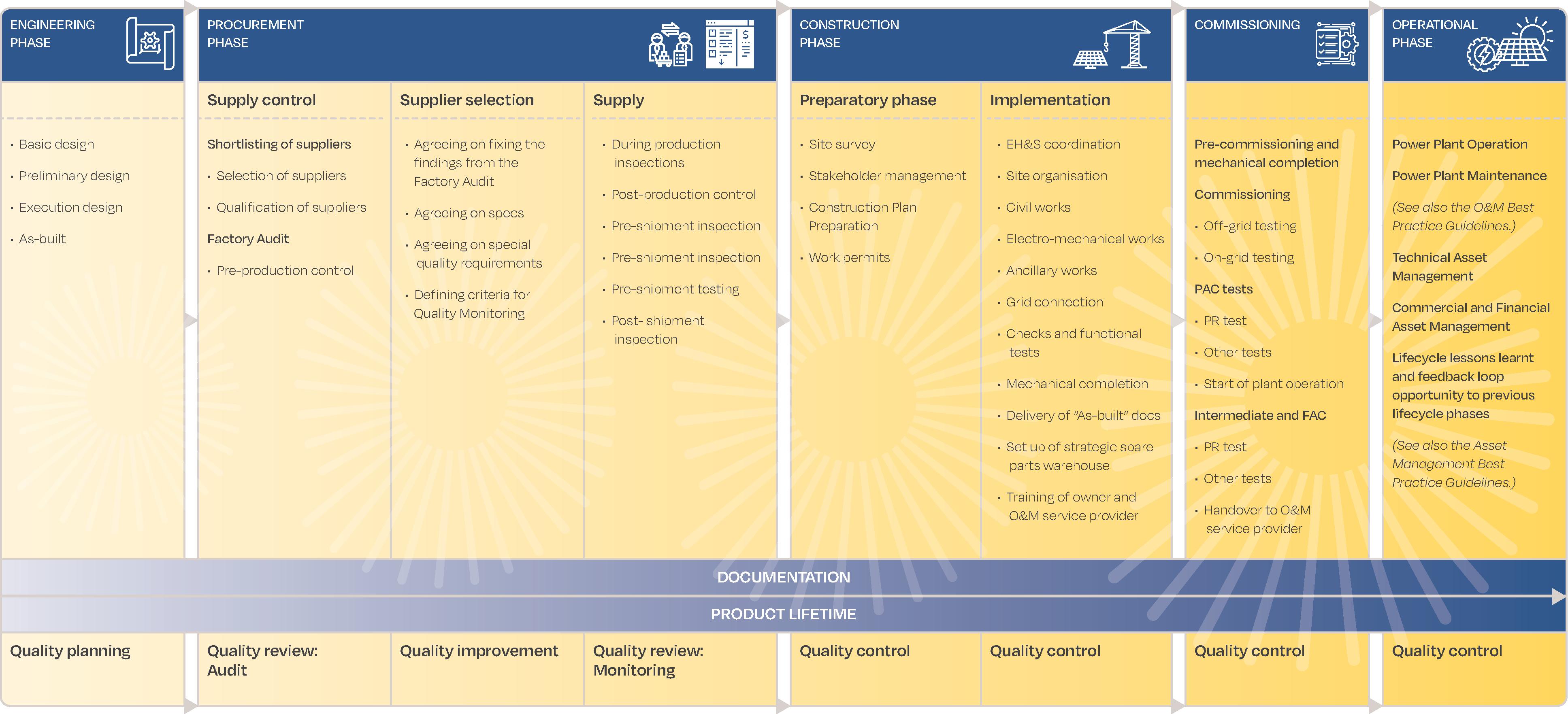

Quality management is key in all phases of LPM, from development to decommissioning. When done robustly, it ensures that a PV power plant works at its maximum efficiency for longer, lowering the levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) and making PPAs cheaper and more competitive. This is crucial to maintaining the growth of solar PV and attracting the necessary commitments and investments to support this. Taking a strong approach to QM will enable the industry to move on from past mistakes and confidently deliver solar plants as part of Europe’s critical energy infrastructure.

Key to effective QM is a strong Quality Management System (QMS). Like QM, a QMS must always be present in LPM, from site selection to the end-of-Life phase and actions should always be flanked by good documentation. A sound QMS can form an important prerequisite for accessing project financing from banks and investors as it minimises the risks of a project. To further boost access to project finance, it is also important to ensure the power plants conform, and are certified to, international standards throughout their lifecycle. There a several international certification schemes and conformity assessment systems available for this. For more information see the Risk management in the operational phase chapter of the Asset Management Best Practice Guidelines and the Risk management in the EPC phase of the EPC Best Practice Guidelines (available at www.solarbestpractices.com).

The four pillars of the QMS as defined in these guidelines are:

- Quality Review (QR)

- Quality Control & Assurance (QC)

- Quality Planning (QP)

- Quality Improvement (QI)

Quality Review

QR consists of a Quality Audit (QAu) and Quality Monitoring (QMo) of component and equipment suppliers. As a recommendation, this pillar should be supported by third-party audit/test firms. The QAu shall take place before a contract is signed. It should ensure that a supplier is capable of delivering on the terms of a contract. The QMo takes place once a contract has been signed and provides an ongoing review of a supplier’s quality management processes. This might be in the form of pre-shipment testing, the commissioning (of parts) of the power plant, or the analysis of the plant performance. The QMo is necessary because an EPC service provider is not in control of a supplier’s quality management processes. It is limited to reviewing the quality performance of the supplier and rejecting or accepting their components based on whether they conform to quality standards within the contract between the two parties.

Quality Control & Assurance

Another pillar of the QSM is the Quality Control & Assurance (QC). This applies more to suppliers as they need sound QC to avoid financial losses from rejections, or claims, and to fulfill their duties towards banks and insurers. It must be ensured that all standards and agreed criteria in a contract are met.

Quality Planning

While QI starts with the supplier selection process, QP will have already started before. While QI is designed to help a supplier improve their processes, QP is designed to help select the right component type. For example, it might be possible to improve the service promise from the supplier for central inverters in remote areas during the QI process. However, it might be a better decision, to design the project with string inverters, as they can be easily replaced with locally stored spare inverters. This shows that an optimised design is of utmost importance. QP begins with site selection, since they can impose significant limitations on project designers’ choices, either through natural or regulatory environments.

Quality Improvement

Using the QAu and drawing on their own experience can help service providers identify possible problems. These issues need to be addressed and actions must be agreed with the supplier, such as implementing better processes, and giving improved (narrower, clearer, more detailed) specifications. This is another pillar of the QSM, QI. This pillar has large cost saving potential, as it helps avoid quality issues.

4.5. Lifecycle lessons learnt and feedback loop

Projects that have reached the operational stages of the lifecycle represent a significant learning opportunity from a technical, contractual, and financial perspective.

The experience and available operational data available can help stakeholders improve their services in two ways:

- Providing realistic, tested, and proven assumptions (both from a technical-operational perspective and from a financial-commercial one)

- Identifying areas of improvement that have created a positive impact on the overall return on investment and plant performance

Carrying out lessons learned from the operational phases is a key tool in identifying ways of improving the efficiency of PV plants. More specifically the feedback loop has proven effective in identifying added value opportunities such as:

- Repeating the yield assessment based on reliable site data, aimed at improving the overall production expectations

- Fine tuning the contracting strategy (simplification of complex or redundant processes set forth in complex contracts, for instance the final acceptable processes)

- Re-defining the scope of work of the main service providers, rebalancing pricing, and risk allocation between stakeholders

- Strengthen the criteria for the selection of key component suppliers and manufacturers

- Increasing the sophistication and appropriateness of the spare parts strategy on a site- and portfolio-basis

To take full advantage of the knowledge created by the operational phases of the lifecycle, a data driven, and analytical approach must be used from the very early stages of operation of the PV plants. This data is vital to establishing and carrying out a meaningful risk assessment and overall review of the PV plant as an investment. This risk driven approach is the foundation of stable operations and reduces the overall volatility of investments in PV plants.