Onboarding Best Practice Guidelines

Certified electrician

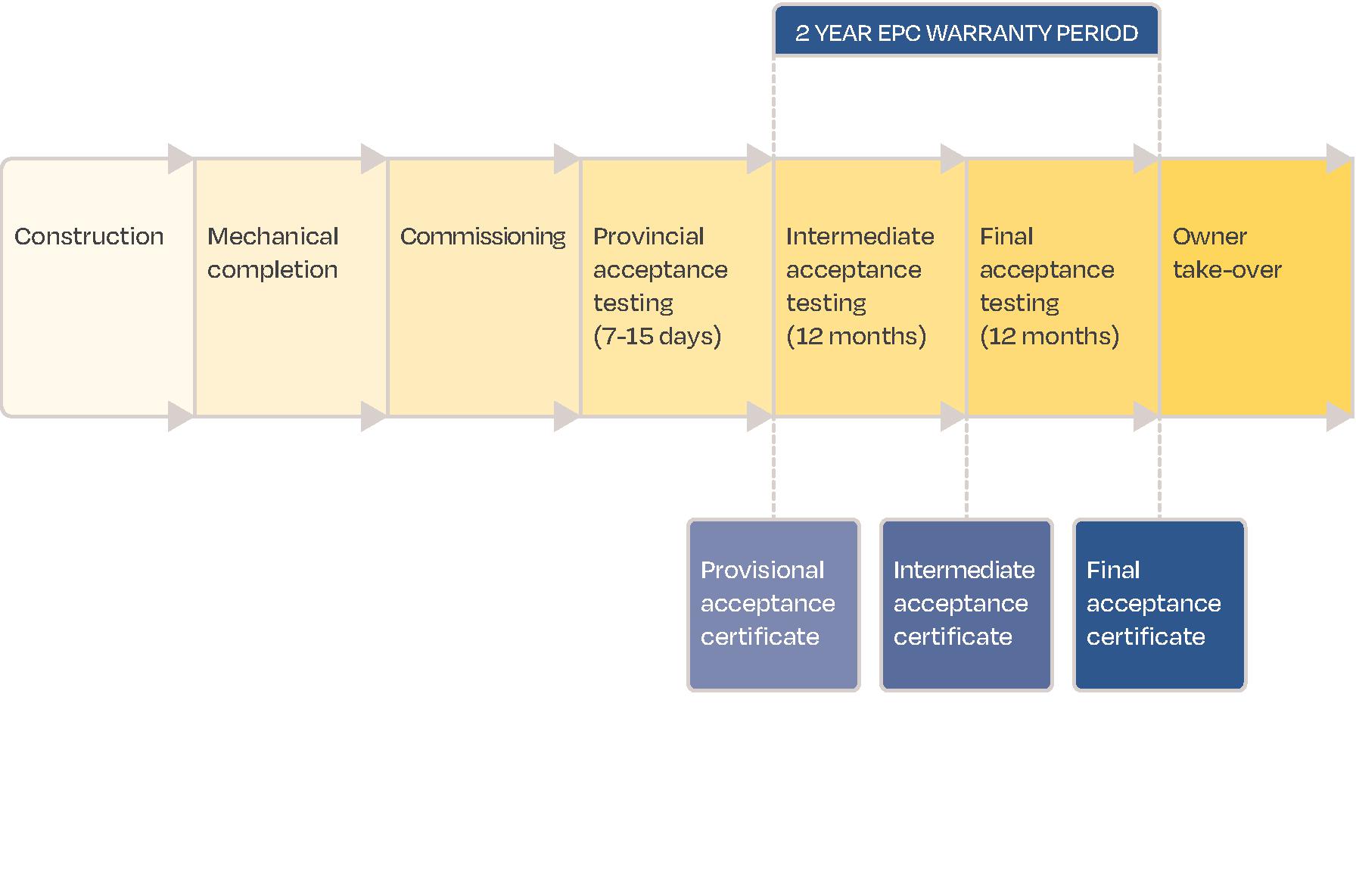

2.1. Construction and operation under EPC warranty

2.1.1. Construction and installation

PV modules

Modules are the engine of the final system and represent a significant proportion of a project’s CAPEX and labour corrective maintenance measures need to be carried out. In the planning phase one should verify that modules are, in theory at least, capable of operating in the given working environment for the anticipated lifetime and with the assumed durability. It is often wrongly assumed that this will be the case if the module type has passed the IEC 61215 / IEC 61730 type / safety approval test. These standards have been one of the most successful contributions to reducing problems in the array field but are only a design qualification standard. They are limited to evaluating known failure mechanisms and assume a moderate climate. Examples of failure modes being missed include backsheet issues or PID and Light and elevated Temperature Induced Degradation (LeTID) related issues. The main impact has been to reduce early failures in the first few years in operation. It does not give any information on the durability of a module, nor does it verify the quality of the product actually being installed, just the general suitability of the product family for the intended application.

Ideally one should verify whether the modules will operate at conditions represented by the tests they have undergone or account for an increased quality risk if conditions in the field are expected to be out of the test standard’s scope. An example of modules potentially operating outside tested specification could be building integrated mounting or systems in arid climate zones, as such systems may run much hotter than they have been tested for. IEC TS 63126 Guidelines for qualifying PV modules, components, and materials for operation at high temperatures gives guidance on testing modules and components for high temperatures. As some standards also allow variants of test conditions based on manufacturer’s definition, reviewing the testing protocol alongside the certificate is recommended.

Integrating testing requirements for PV modules in the procurement conditions allows for claims against underperformance as well as identifying design deficiencies. PV modules from one system supplied by various production sites or batches may require separate assessment.

There are three groups of quality tests described:

1. Performance characterisation testing

2. Qualification testing

3. Module Reliability Tests (Stress Tests, Accelerated Aging Tests)

Performance characterisation testing mainly addresses the electric performance of the PV modules and the condition of the cell interconnection circuit (cell cracks or interrupts). Regarding the power warranty, the performance of the entire delivery can be deduced from a random sample according to ISO 2859-1. As budget and timing is usually critical, mostly General Inspection Level based on the total number of modules per production batch is applied. As an alternative, a combination of a smaller sample size (e.g., 50 per batch) and the manufacturer’s flash list will allow a robust product verification if the measurements have been carried out with a sufficiently low uncertainty and the service provider has an appropriate quality system. It is advisable to combine power measurement with electroluminescence imaging for crack detection. The performance at low irradiance is something needed for the energy yield calculation, but samples size can be small (e.g., S 1). In the absence of third party verified PAN files it is advisable to base PAN files on independent measurements as simulations based solely on data sheet information may lead to high uncertainties in energy yield simulation.

Product qualification tests are typically destructive or longer-term tests and sample sizes are kept smaller. It is important to perform tests on modules that represent the material combinations (bill of materials) of the module type. The tests shall check the functioning manufacturing processes, the production control and are helpful in determining general workmanship. Some suitable qualification tests are defined in the standard IEC 61215-2, which is the basis for type approval and design qualification of PV modules. The sampling method is typically Special Inspection Level S 1 to S 3 acc. to ISO 2859-1 with consideration of all bills of materials and potentially different production lines to be represented. Induced degradation tests (such as PID and LeTID) are screening tests and are suggested if sufficient proof of resistance to such degradation is not provided. Here sampling rate could be reduced to two modules per bill of materials to minimise testing cost.

Product reliability tests shall evaluate the long-term behaviour with a focus on module performance but also on electrical safety. Several test sequences for investigating a module’s resistance to environmental conditions, such as high UV level, strong temperature changes, high temperatures combined with high relative humidity and mechanical stress both from wind forces and snow loads are described in IEC TS 63209 Photovoltaic modules - Extended-stress testing - Part 1: Modules. Depending on the application and the project region the stress level may vary. The suggested sample size is two modules per test and bill of materials. In particular polymeric material degradation has caused major reliability concerns in the recent years. Here the technical specification, issued in 2021, provides a combination of damp heat testing, UV testing and thermal stress in its sequence three that is designed to screen for long-term backsheet failures.

Inverters

The inverter is one of the most complex components in a PV power plant and includes multi-functional power electronics for optimising the power output. This element is the interface with the grid and reads and communicates operational data to the monitoring system. A fault with the inverter leads to an immediate decrease in power output, which grows in proportion to the size of the inverter. Owners should not simply rely on data sheets but invest in quality review services, conducted by experienced technical advisors. In a quality assurance process, the key steps of design, manufacturing, installation, and commissioning are independently evaluated, to prevent potential issues that could decrease performance across the inverter’s lifecycle.

The key risk mitigation steps are a factory audit, the review of a manufacturer’s factory-out inspection and the commissioning, which are presented in sections 7.3. Supply review. and 7.4. Delivery.

Aside from the general comments above, key areas for potential issues with inverters include:

· Adaptation to voltage and power design

· Isolation issues

· Blocked air vents, filters etc.

· Derating characteristic of inverters, high temperature shut off

· Rating or spacing not suitable for location (e. g. high altitude)

· Grid code compliance

· Unavailable required national certification

· Inverter metrology

· Interference with radio signals etc. (electromagnetic compliance and adaptability)

· Optimisers

· Local transportation including unloading opportunities

· Local service

Inverters need to be chosen depending on system topology. There is no formal assessment available currently, but a risk assessment when choosing a system topology considering performance, maintainability, impact of failures, likelihood of failure and reparability. As an example, a central inverter may have a higher efficiency, be cheaper to install, but in case of a failure takes down the system and will take weeks to repair, while spare string inverters could be stocked, and any failure could be corrected in a short time. The evaluation of risks will depend on design objectives, but it should be documented for later verification and any future process improvements.

When planning a system, it is critical to match the operating characteristics of the inverter (efficiency, load-related derating, voltage window) to the real operating conditions.

Sufficient diligence needs to be exercised when it comes to:

· Specific requirements for inverters, e.g., compliance with (EU) 2016/631 for Europe

· Performance characterisation testing (INV File generation for energy yield simulations)

· Product qualification testing

· Product reliability testing according to appropriate standards

Electric general and technical lead

A. Construction

In this phase, the solar power plant is installed based on installation manuals provided by suppliers to assure the proper storage, handling and installation of mounting systems, PV modules, inverters, transformers, cabling, monitoring system/sensors and other balance of system components. It also ensures the quality of the installation as well as the long-term stability of the PV system.

A proper schedule and preparation of several activities around the construction are important and should preferably be organised according to common project management techniques. This includes clear definition of objectives, activities, and responsibilities (who does what?), time plans and milestones (when?), cost planning, and quality assurance. To achieve this, an effective and efficient communication, documentation and reporting flow between the Asset Owner, the EPC service provider and the subcontractors is necessary. This will help encourage accountability, potential construction defects are promptly identified, high standards upheld, and monitoring the EPC service provider’s performance is easier.

The overall construction activity can be divided into two phases: firstly, the preparatory phase, related to the preliminary activities and secondly, the construction implementation phase, including site preparation, civil, mechanical, and electrical works necessary to complete the plant and bring it to the production phase.

Construction preparatory phase

The construction preparatory phase includes those planning and preparatory activities that ensure the smooth realisation of the PV plant. For this purpose, it is important that the construction project is correctly set up according to project management principles: the Asset Owner and the EPC service provider define project organisation and objectives, arrange main parts of the project in a work-breakdown structure (WBS), deduce a time schedule with clearly defined work packages, including responsibilities/accountabilities (responsibility matrix, for example, a RACI matrix), interdependencies, duration and resources. This time schedule shall be the reference for monitoring the project’s progress from both a physical and cost control perspective and needs to be regularly updated.

Site survey

The site survey aims at checking that there are no physical and geographical constraints or inconsistencies with the assumptions and technical details defined in the Execution design (see Chapter 6 on Engineering). If there are inconsistencies between the execution design and the site survey, the EPC service provider should consider doing another topographical survey with a drone.

The survey is also necessary for checking the actual status of the site and for planning the preliminary activities necessary to prepare the site for the mobilisation of personnel and equipment and the start of the main construction activities.

While the effective mobilisation of the EPC service provider and their subcontractors usually takes place once contracts enter into force (in general when a notice to proceed is issued by the Asset Owner), the execution of certain early works, sometimes also called preliminary works, is a project strategy that is becoming more frequent.

With reference to construction activities set-up, the key topics to be investigated during the site survey are:

· Mapping of the construction site (allotment and boundaries, topography, etc.)

· Definition of the area for temporary facilities and storage/warehouse

· Identification and mapping (geolocalisation) of interferences to be considered during construction, for which drones can be used

· Assessment of critical elements for construction and identification of mitigating actions (technical risks, rests of bombs, hazardous waste, but also archaeological discoveries)

· Detailed survey of transportation facilities and routing and other logistic items

· Execution of the pull-out test, necessary for the final test of the selected foundation design of the mounting structures.

Stakeholder management

The primary tool for understanding the context in which the project is implemented is to identify and understand the stakeholders involved in, or affected by, the project. This allows one to become aware of their expectations and to determine the effective, potential, or perceived impact that the project can have on them identifying methods for involving them.

The identification of the stakeholders and their needs and expectations requires suitable knowledge of the relationships that exist between the different actors that are present and active in a given context. For this purpose, all subjects that could influence or be influenced by the project must be considered.

It is important that the identification of the stakeholders is not limited to local and administrative authorities but should also consider people and organisations that are relevant for local communities, as they represent their interests and identity.

Construction preparation plan

Construction Planning aims at planning all construction activities properly and guaranteeing that resources are available and scheduled consistently with activities. This avoids any unplanned stops.

After definition of the project scope of work, the project management team structures the project by organising the activities in a hierarchical structure, the Work Breakdown Structure (WBS). Only the activities identified with the WBS shall be within the project scope and, therefore, can be planned and controlled. There is only one WBS per project. A well-defined WBS:

· Provides complete definition of the project scope at different levels

· Allocates tasks and responsibilities

· Defines a numbering system, which is used as reference in project plans, reports, and technical documentation

· Provides an input to integrate cost and schedule data

· Ensures the alignment with the contracting execution strategy

· Facilitates the roll up of cost, progress, and schedule performance information for reporting purposes.

All parties (the Asset Owner, the EPC service provider and other service providers) involved in the project should comply with the WBS and related coding system. Clear and effective communication between the Asset Owner, the EPC service provider and other service providers (and in general, all third parties involved in the project), and constant monitoring of the construction work progress according to the WBS, are key to ensuring full alignment on scope of work, objectives, deliverables, and timing.

WBS’s lowest hierarchical items are the work packages (WP). By defining each WP in detail and considering dependencies, the project plan is created. Each WP should contain at least the following information:

· Name

· Unique number/code

· Version and status information

· Description of content and results to be obtained

· Prerequisites and dependencies (deliverables required etc.)

· Projected duration

· Resource requirements (people, material, tools, vehicles, etc.)

· Person responsible for the WP

A detailed scheduling of the activities, including milestones, is essential to completing the work in a timely manner. Proper scheduling of the works is mandatory for correctly managing and controlling the progress of the project. If the work plan has not been prepared appropriately, mistakes and delays cannot be identified, and corrections cannot be implemented. Furthermore, the project plan needs to be updated regularly.

Project managers derive subordinate plans and documents from the central project plan. For example, the EPC service provider and other service providers will have planning, scheduling, reporting, and documentation obligations, according to the stipulated contract. With reference to the WBS, contractors should be responsible for the lower-level activities schedules and plans. A typical document for this phase is the mobilisation plan, which includes:

· Construction site organisation chart: the subcontractors (civil and electro-mechanical) need to provide the construction site organisation chart which indicates all the expected positions, the staff residence times and the expected hours.

· List of site vehicles and equipment: subcontractors must provide the list of vehicles and equipment they intend to use for different kinds of work, accompanied by certificates of suitability and maintenance and/or testing sheets.

Work plan and mobilisation plan guarantee in-time arrival and accommodation of construction site personnel and assembly materials. They also ensure that the different elements of the construction phase are properly coordinated.

Based on the defined project schedule (baseline), the associated physical progress curve should be determined, to establish a reference plan for the percentage of physical completion of the project at each date. This is key for proper project monitoring.

To calculate the project’s physical progress, one must define specific calculation rules to apply to each elementary activity type, as well as determine the weighting criteria.

The construction plan should also define processes and procedures relating to the interface of the construction team with the rest of the project staff, in particular with the engineering, EHS and quality management teams. It should be assured, for example, that all the project changes proposed by the EPC service provider and other service providers are checked and approved by engineering department (change management). Furthermore, the construction activities should be verified in accordance with the quality control plan and HSSE procedures (quality management). Other control activities concern cost/budget, HSSE compliance, documentation, etc.

Check and finalisation of working permits

Country-specific legislation and regulations around HSSE and construction activities are continuously evolving. It is critical to be sure that all works, administrative permits, and authorisations have been obtained to avoid breach of any legal provision. Such a breach could result in severe consequences, both in terms of personal and administrative sanctions and in downtime and delay in the execution of the activities.

A useful tool to ensure full compliance is the prescription and authorisation checklist which should identify all the relevant legislation and regulations applicable to the specific project and location. It also lists all requisites necessary to start the construction activities (authorisations, particular training requirements for certain works, such as works at height, land lease agreements, etc).

Activation of external suppliers (services and materials)

Once all preliminary activities have been assessed and completed, the construction activities are ready to start. All subcontractors and suppliers must be activated according to the specific clauses of the relevant contracts and based on the scheduled activities. The scope of this phase is to ensure that all resources are present at the site in a timely manner to avoid any downtime and delay.

Construction implementation phase

Construction site activities must be supervised by the EPC service provider’s Construction Manager. They should coordinate with the Asset Owner’s Construction Manager and the Construction Supervisor on the monitoring and control of subcontractors. Throughout construction, drone construction monitoring flights should be carried out periodically to monitor, record and report on construction progress and quality. The data from these scans can also provide valuable support to H&S, stock management, and adherence to local planning and environmental regulations.

Construction site organisation

Construction site organisation refers to the preparation of the site for the start of civil, mechanical, and electrical works.

The effective mobilisation of the EPC service provider and related subcontractors usually takes place approximately 60 days from the signature of the contract. However, preliminary site preparation and executive engineering may begin immediately after signing.

In the mobilisation phase, contractors will begin to mobilise direct and indirect labour, equipment and means so that all planned activities can start as scheduled.

Site preparation main activities are:

· Opening of the construction site

· Archaeological survey may be requested by local authorities depending on the historical interest of the site

· Removal of vegetation removal and the superficial part of soil where foreseen (this kind of activity should be minimal in accordance with a positive biodiversity strategy)

· Staking and beating of the poles of the structures

· Visual mitigation works planned.

Civil works

Civil works refers to excavation for the construction of cable ducts, including foundation, MV overhead line supports, preparation of the areas where inverters and DC boxes will be installed, distribution station, road construction, and any earthworks in general.

They must be planned and implemented to minimise the interference and the overlap with the electro-mechanical activities described below, which are often difficult to manage from a safety point of view.

Biodiversity issues need to be considered to minimise the impact of civil works. Where this is not possible, restoration or compensation measures should be taken, but it is always better to reduce destruction during works. Raising the awareness of personnel and clear guidelines can help to achieve this.

Electro-mechanical works

Mechanical activities mainly consist of:

· Withdrawal of materials from the Contractor warehouse

· Assembly of metal structures

· Installation of PV equipment / panels

· Package / cabin assembly

· Tests and inspections

Electrical activities mainly consist of:

· Laying ground network (equipotential bonding)

· Laying DC (LV) solar cabling and related components for connecting PV module strings to inverters using tools certified/qualified by the manufacturer for PV cable-connectors assembly. At present DC cabling configurations can vary a lot but nevertheless, laying DC cabling is a key element of the electrical works

· Laying MV cables from transformer stations to the distribution station

· Laying LV auxiliary cables

· Cabin and field connections

· Tests and inspections

Ancillary works

Ancillary works are activities that are not directly connected with the assembly of the “electric generation plant”. They refer in general to security (fencing, CCTV, lighting, …), vegetation care, internal roads, signposting, and so on and so forth.

These works, even if not prioritised, must not be underestimated because they could delay the handover of the entire plant.

Grid connection

Utility scale PV plants need to be connected to the network, usually managed by the Transmission System Operator (TSO). Connection complexity depends on the distance between the plant and the substation, its conditions and the technical solution identified for the connections. These works are the final stage of the construction activities and normally require the involvement of the TSO, which should be scheduled well in advance.

Checks and functional tests

Once the plant is completely built and connected to the grid, one must test that it works properly. It is important that tests are carried out according to a detailed procedure agreed between the EPC service provider and the Asset Owner.

To this end, the EPC service provider must send the Asset Owner a detailed plan of execution of all the work necessary to reach Start-up (Start-up Plan), before the start of the Mechanical Completion and Pre-Commissioning activities of the plant.

The plan should include the following minimum requirements:

· Definition of a start-up team

· Definition of the project functional units and related sub-units

· Definition of the plant sections that can be put into production in sequence

· Definition of the schedule and procedures for carrying out the preparatory tests for the start-up for each functional unit and plant section

· Description of how to perform the Mechanical Completion and Pre-Commissioning tests on the functional units

· Description of the execution of the Commissioning tests on the functional units and on the entire system

Mechanical completion

When the plant is completely built and connected to the grid, after a visual inspection, the Asset Owner issues the Mechanical Completion Certificate (MCC).

The aim of the visual inspection is to verify:

· That all components and materials are present and in accordance with the project documentation

· The compliance of the completed project with the project documentation, the Technical Specification, and the current legislation

· The electro-mechanical completion of the plant

· That all components are free of visible damages that could compromise the safety of the components and personnel

· That the components have been installed correctly

· The correct identification and labelling of all components such as inverters, DC boxes, cables, support structure rows, switches, communication devices, monitoring elements, etc.

· The correct execution of the connections

· An aerial survey to validate the asset against its design layout

Training of Asset Owner and O&M service provider

As soon as the plant is ready for operation, after MCC has been issued, the EPC service provider should arrange for a specific training for the Asset Owner and the O&M service provider’s personnel (that could be a third-party or the O&M division of the EPC service provider). This training can transfer the knowledge and philosophy with which the plant has been designed and constructed.

Training is important as it allow the O&M service provider’s staff to familiarise themselves with the plant and its operations. Poor training standards can result in lower performance of the plant, due to delays in detecting system malfunction signals, resulting in longer downtime as faults are resolved. This is also an opportunity for the O&M service provider to give feedback to the construction (and engineering) team, especially if both belong to the same company.

The Asset Owner’s personnel should also receive training. This will help avoid misunderstandings between the Owner and O&M service provider and make their collaboration more efficient and effective.

A comprehensive and detailed as-built documentation (Annex E), manuals and procedures (Annex C “Documentation set accompanying the solar PV plant” of the O&M Best Practice Guidelines) should be part of the training activities. For more information on the handover to a specialised O&M service provider, please refer to Chapter 10 on Handover to O&M.

B. System Commissioning

System commissioning is one of the most important stages of the EPC service provider’s work as it closes the construction period and prepares the PV plant for commercial operation. This crucial step of the project includes performance and reliability tests. These make sure that the PV plant is built according to the international standards and industry best practices, and that it complies with the requirements as agreed with the Owner, grid specifications and guaranteed performance levels. Tests are undertaken for all individual components from checking that components function to more detailed measurements and verifications of the overall system. Successful commissioning and timely achievement of the Commercial Operation Date (COD) is linked to the release of a milestone payment as defined in the contract as well as the release of the performance bond. It is, therefore, very important that the contract clearly describes the requirements, criteria, documentation, and reporting required to complete the EPC service provider’s scope of work and handover to the Asset Owner and the O&M service provider’s team.

Pre-commissioning

Mechanical completion happens the final construction stage meaning that all principal components that are part of the PV plant have been erected or installed. At this point, the EPC service provider will usually conduct a detailed inspection of the works, possibly accompanied by the Owner or any third-party representative (such as a technical advisor). This option should be clearly stated in the EPC contract clause referring to commissioning (if the Owner intends to apply it). Activities carried out under pre-commissioning should be detailed and agreed in advance with the Asset Owner in a specific document.

The pre-commissioning activities fall within the construction phase and are mostly undertaken in parallel to the last steps of electro-mechanical works. In large scale projects, the first blocs are ready under pre-commissioning while other parts are still being erected.

The pre-commissioning phase includes the following main activities:

· Systematic compliance checks performed on each component of each system, performed in a non-energised state

Testing of appliances, energisation of cables, testing of instrumental circuits, testing of circuit breakers, etc During the pre-commissioning phase, the following tests should be performed, as a minimum requirement:

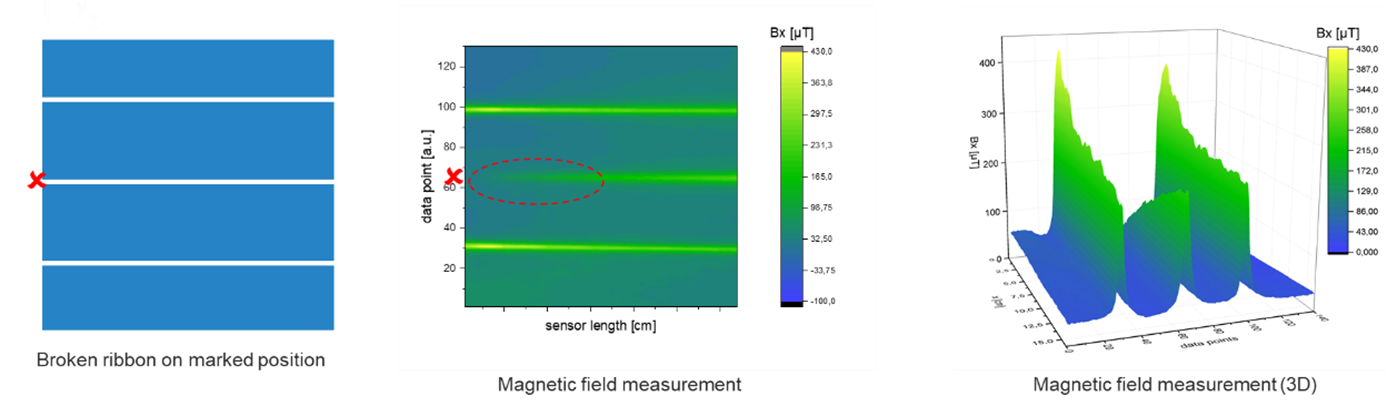

· Mechanical integrity of the modules with visual inspection and the correct wiring. Thermographic analysis (via drones) can be added at this stage as a best practice

· Verification of the nominal power of the installed system carried out as the sum of the nominal power at STC of all the installed modules

· Verification of the correct operation of all auxiliary services (fire system, rodent protection, forced ventilation of transformers, temperature sensors, UPS systems and related storage systems, lighting systems, etc.)

· Control of all input signals to the SCADA system

· Verification of all power supplies of the auxiliary services of the cabins

· Commissioning of UPS systems and related storage systems, SCADA system and of weather stations and environmental sensors

· Verification of IP addresses on all equipment

· Setting of all alarm thresholds on the equipment

· Verification of the correct polarity and electrical continuity of all the strings

· Check all electrical connections

· Completion and functional verification of the earthing system.

After execution of pre-commissioning activities, the plant will be ready for energisation and for the commissioning activities.

Usually, a detailed checklist covering all components and parts is used to make sure that nothing is missing or incomplete. The works are thoroughly checked through the following items:

· Inverters

· Modules

· Foundations

· PV Module Mounting Structures

· LV and MV Cabling

· Transformers

· Protection, distribution centres and switch gear at the substation

· Combiner boxes

· Civil works

· Low and medium voltage installation works

· Monitoring and security systems

Finally, the checklist should be provided to the Owner and their advisors, together with the compilation of an initial list of construction defects (commonly referred to as a “punch list” or “snagging list”). Counterchecking the EPC service provider checklist and providing own observations and items to add, as defined by the Owner or their advisors, is recommended. . This punch list should include only minor finishing works, the cost of which usually equates to a small percentage of the overall contract value. The contract also needs to specify the timeframe for correcting punch list items, and what the conditions are for granting Provisional Acceptance if punch list items remain unfinished. Once the punch list has been issued by the Owner’s representative a meeting is required between them and the EPC service provider to agree specific resolution for each item and determining if any items are disputed.

Mechanical completion allows for further testing activities to commence. In large scale projects, this is often undertaken by batch and delayed over time, as different parts of the plant are in different stages of construction.

Commissioning, off-grid, and on-grid tests

Commissioning activities

Commissioning activities include operational checks and tests executed on energised electrical systems. The Test Protocol must be agreed between the parties before the start of the tests as part of a Start Up Plan, defined before the start of the Mechanical Completion and Pre-Commissioning activities.

The Test Protocol must respect all the requirements contained in the contract and its basic content should include:

· Results of the visual inspection and related checklist

· Test methodologies

· Instrumentation used for testing

· Test program

· Test conditions

· Test data

· Results of the Pre-Commissioning and Commissioning tests

· The start-up protocols issued for the key components (inverters, transformers, etc.)

This testing aims to verify and certify that the plant has been constructed professionally, according to the pre-established technical prescriptions, and in accordance with the project and any approved variants.

Before the plant is energised, a series of functional tests and measurements should be undertaken as per the reference norm IEC 62446: Grid connected photovoltaic systems. Minimum requirements for system documentation, commissioning tests and inspection for all electrical commissioning.

The testing procedure should be handed over to the Owner prior to commencing the tests, as is usually defined in the EPC contract. This allows the Owner or advisors to review and comment on the testing procedure before implementation. At the end of the commissioning phase, the EPC service provider submits a Test Protocol to the Asset Owner, summarising the results of the Pre-Commissioning and Commissioning tests.

The following test regime shall be performed on all systems. Any test indicating a fault should lead to default rectification and re-testing of the components.

On the AC side, all AC circuits, including AC cables from inverters to transformers, transformers themselves, and main MV switchgear should be tested according to the requirements of IEC 60364-6.

On the DC side, the following tests shall be carried out on the DC circuits and components forming the PV array:

· Continuity of earthing and/or equipotential bonding conductors, where fitted

· Polarity test

· Combiner box test

· String open circuit voltage test

· String circuit current test (short circuit or operational)

· Functional tests

· Insulation resistance of the DC circuits

Some expanded test, not mandatory but often included in the EPC service provider contractor scope, can also be carried out to ensure the best system performance and reliability:

· String I-V curve measurements on a selected sample (10% of the plant at 500W/m²)

It is a best practice to take a pragmatic approach to tests which require minimum levels of irradiance. String tests and thermography should be carried out above certain irradiance minimums. Conducting them at lower levels will provide reduced value from the results. If necessary, some tests may need to be deferred until high season to be valid.

In addition to the above electrical tests, all other equipment should be tested according to the manufacturer’s guidelines and industry best practices to ensure that it functions properly before the energisation of the PV plant. All other equipment and materials include:

· Meteorological stations and monitoring system

· Low voltage installation, civil works, and medium voltage installation

· Security system as well as cyber-security system

· Sanitary system

· Firefighting system

Off-grid testing

The first tests to be conducted are the polarity and combiner tests which need to be undertaken while all strings are still disconnected.

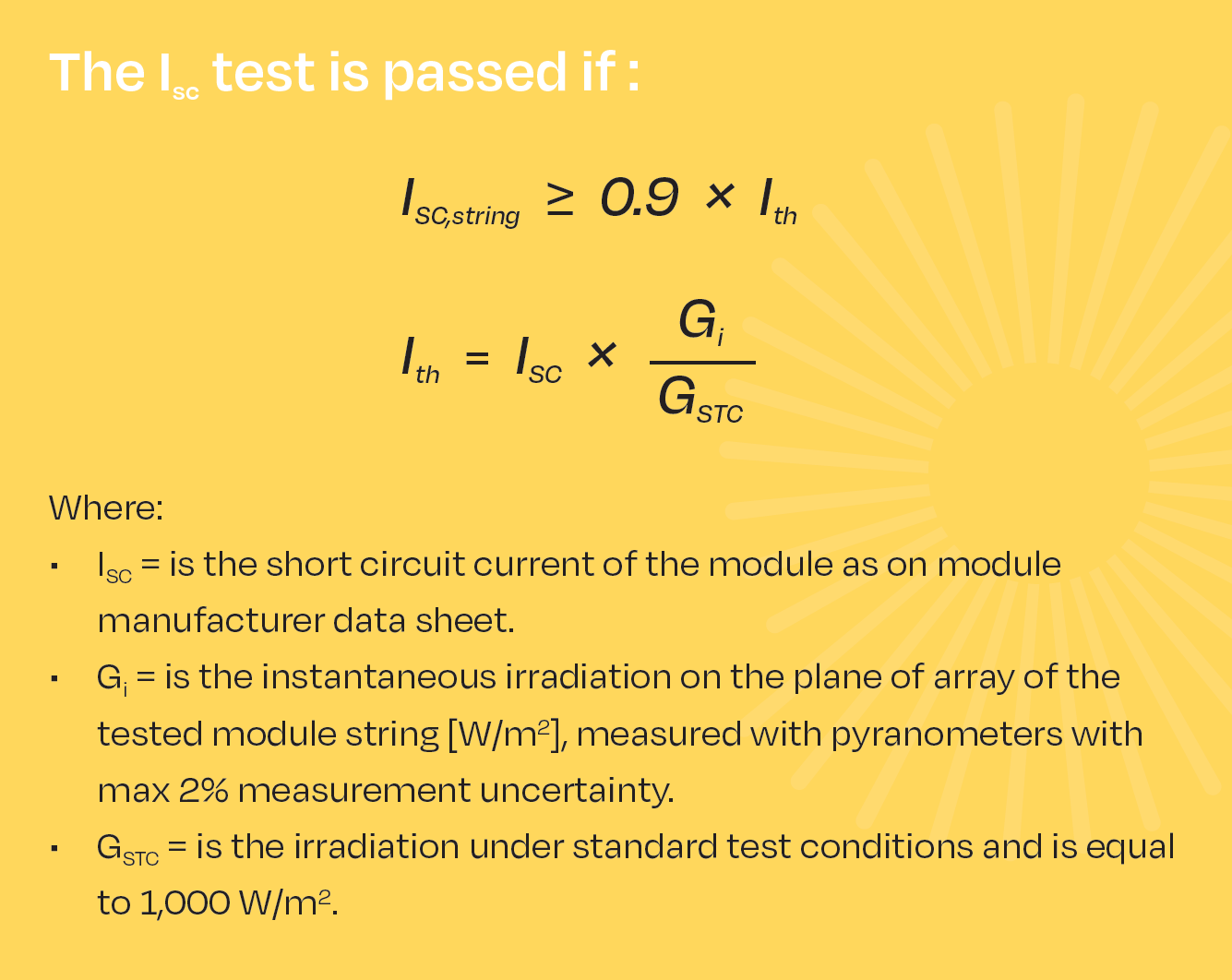

The off-grid tests should include measuring 100% of the open circuit voltage (Voc) and the short circuit current (Isc) of the module strings according to IEC 62446. Prior to starting testing, the Owner must confirm the adequacy of the measurement devices to be used by the EPC service provider (measurement uncertainty, calibration, etc.). A report with measurement results from all the strings will be presented by the EPC service provider in digital form, as an Excel file.

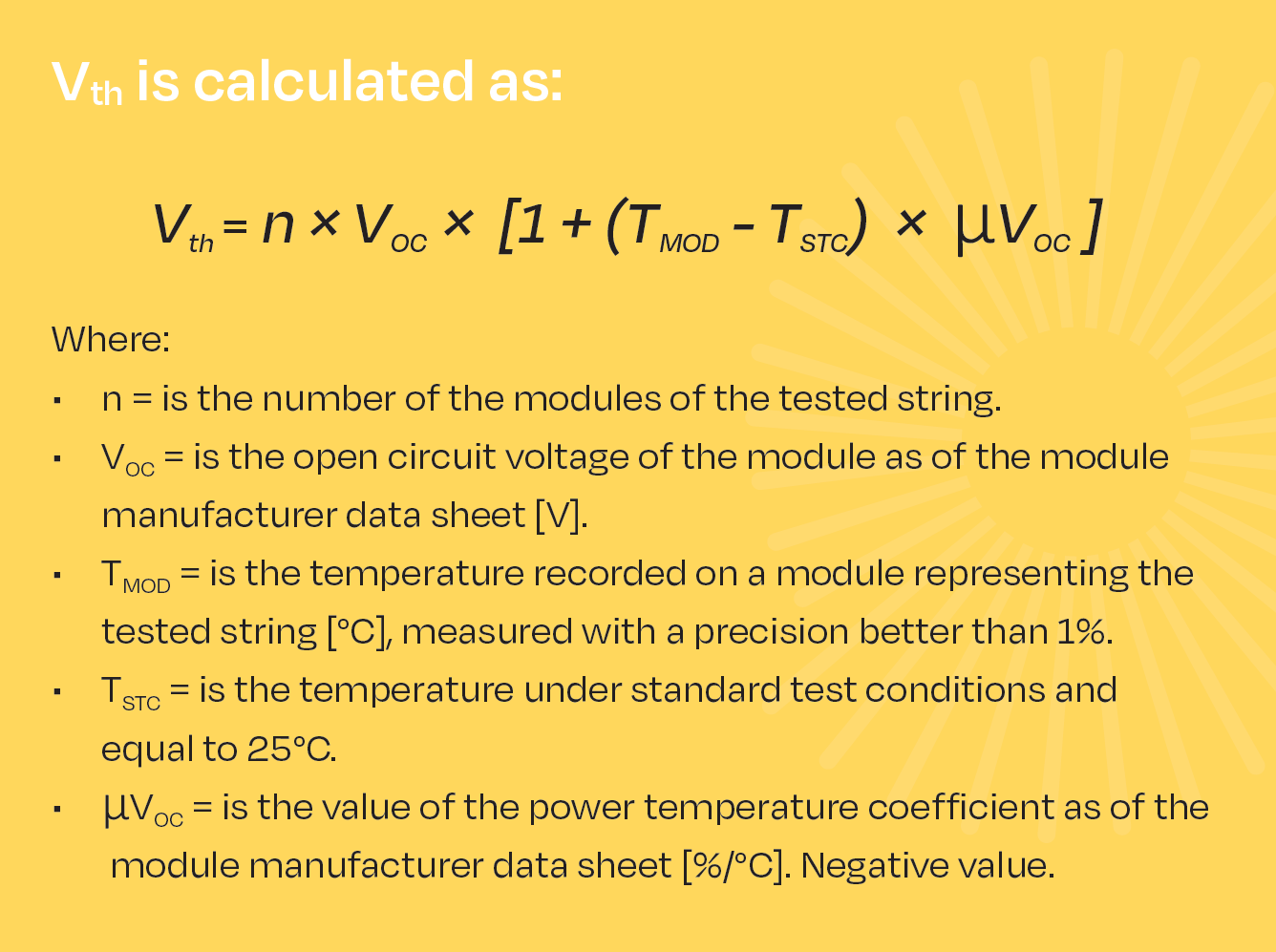

The VOC test is passed if all the VOC, string on the tested strings is within 5% of the expected value derived from the module datasheet. Note that most of the time, the theoretical value should be adjusted with the actual temperature recorded at the time of the measurements as it may be far from STC (25°C).

A commonly used formula is:

Where Vth is the theoretical open circuit voltage for the strings and calculated as follows:

The Isc test is passed if all the Isc,string on the tested strings satisfy the following condition:

It should be noted that the short circuit current test is not intended to detect system underperformance but only used for fault detection in string cabling.

Once the commissioning phase of all the plant sections has been completed and the protocol test issued, the Ready For Start Up (RFSU) certificate of the plant is released by the Asset Owner and then the On-Grid performance and functional tests can be started.

On-grid testing

Once the above off-grid tests have been successfully performed, the PV plant can be energised at inverter level and main switchgear level at the point of interconnection with the grid. The EPC service provider shall demonstrate that the overall system and equipment operates in accordance with the:

· Equipment manufacturer specifications especially for inverters, transformers and MV equipment

· Grid Connection Agreement which should be annexed to the EPC contract, or at least its technical annexes regarding testing and commissioning specifications

· Specifications set out in the EPC Contract

· Any relevant Applicable Standard, mainly IEC 61727 and local grid code

Inverters and transformers shall be commissioned by their manufacturer or an authorised representative of the manufacturer, using the manufacturer’s specified procedures. Commissioning reports shall be issued in a format provided by the manufacturer.

All SCADA system equipment shall be commissioned and tested using the manufacturer’s specified procedures. Tests shall verify the correct operation of the SCADA system, meters, sensors, weather station instruments, and all inverters, while verifying the correct data input logging from trackers (if any), breakers, and other components monitored by the system. The SCADA system shall be fully remotely accessible. A SCADA system commissioning protocol or report shall be provided.

Before energisation, the EPC service provider shall verify the completeness of the substation and the correct installation of all components. A detailed inspection of the substation shall be executed. The testing and commissioning of the PV plant substation connection to the grid system should be performed, including but not limited to:

· MV equipment

· Control and Monitoring System

· Protection system

· Telecommunication system

· Metering devices

· Auxiliary supply equipment and back-up (UPS, diesel, etc.)

In some countries, compliance with the grid code and local safety standards need to be validated by an independent body, and a certificate provided to the grid operator to allow power injection. These compliance tests may also be carried out by the grid operator themselves.

Prior to achieving Provisional Acceptance, it is common practice to carry out module thermography, using aerial inspections as best practice. 100% module thermography should be carried out at this stage according to IEC 62446-3:2017. Issues identified from this inspection will need to be resolved to pass PAC. These inspections and the reports generated should form part of the handover documentation.

Provisional Acceptance Certificate

The Provisional Acceptance stage marks the end of the construction works and obligations of the EPC service provider. It means the Asset Owner is giving their conditional acceptance of the works. This triggers the two-year standard warranty period, across which the EPC service provider must prove a minimum level of performance from the PV plant, as defined in the contract. At this stage, the plant is also handed over to the Owner and the O&M service provider which may be the same company as the EPC service provider or a third-party.

The conditions for issuing the PAC may differ from contract to contract but the key elements are as follows:

· All commission tests have been successfully completed, including Mechanical Completion, grid connection and energisation of the plant

· The noncritical punch list items have been identified and signature have been provided for corrections. The value of this remaining work does not exceed a certain proportion of the contract price (typically 2-5%)

· The Provisional Acceptance performance tests have been passed (PR but also functional and capacity tests in some cases)

· All equipment and sub-contractor warranties are transferred to the Owner

· The EPC service provider has provided the Owner with the initial or minimum stock of spare parts, as defined in the contract

· All as-built documentation has been provided to the Owner

· Training of the O&M service provider’s teams has been performed and relevant O&M manuals issued

· Liquidated damages (LDs) related to performance or delays have been paid by the EPC service provider

· Any performance security or warranty bond required during the EPC warranty period has been delivered to the Owner

The PAC is signed off by the Asset Owner and, if stipulated in the contract, can also be validated and signed by an independent advisor.

Performance Ratio test

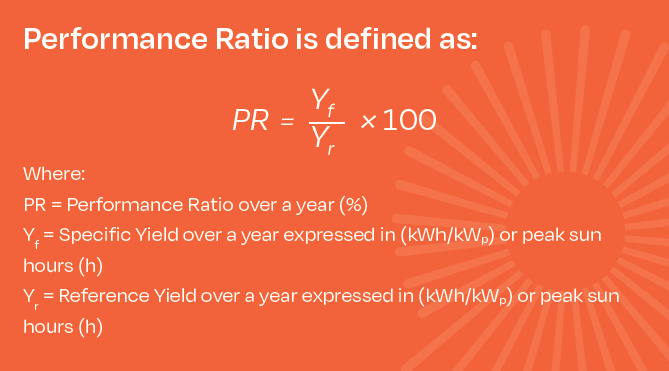

After the functional test, the PV system’s performance, in terms of energy and power, is evaluated in the Start-Up phase. To validate the PV plant performance at Provisional Acceptance phase, the PR test is conducted over a limited period and compared to the guaranteed PR, set based on simulations. The usual duration of PR tests is 7 to 15 days, depending on the contract. From an Owner’s perspective, having the longest testing period possible is recommended, as this helps to check performance in a wide range of climatic conditions, and facilitates comparisons with simulated values.

Usually, the testing period needs to fulfil minimum requirements regarding weather conditions and plant availability such as:

· Minimum irradiance threshold in daily values on a certain number of days (e.g., 8 days over a 15-day period with irradiance greater than 5kWh/m²/day) which should be adapted depending on the season of the test and specific conditions of the project location

· Minimum irradiance threshold on a single day for consecutive hours (e.g., irradiance over 500W/m² during at least 3 consecutive hours in 8 days over a 15-day testing period), also to be adapted to the season and project location

· Total number of testing hours with irradiance above a certain threshold (e.g., 500W/m² for at least 20 hours in a 15-day period)

· Availability should be 100% during the testing period at least at inverter level. Grid availability should also be 100%. The SCADA and the environmental monitoring system must also guarantee 100% availability of data throughout the test period

If the above conditions are not fulfilled within the testing period, it is generally extended until they are. Conditions should be set pragmatically and potentially adjusted to avoid delaying the PAC and leading to difficult negotiations and distrust between parties. The time of year should be considered so that unrealistic thresholds are avoided. The performance tests should ideally be performed during spring as this is usually when performance is at its peak due to better weather conditions. Poor weather conditions can penalise performance compared to simulated values (high summer temperatures, winter shadows or low irradiance).

If the continuity of the test is interrupted due to faults or events related to the malfunction of the plant or one of its parts, the test will be suspended and repeated from the beginning.

If the causes of the interruption are not attributable to the EPC service provider, the test will be suspended and will resume at the end of the interruption.

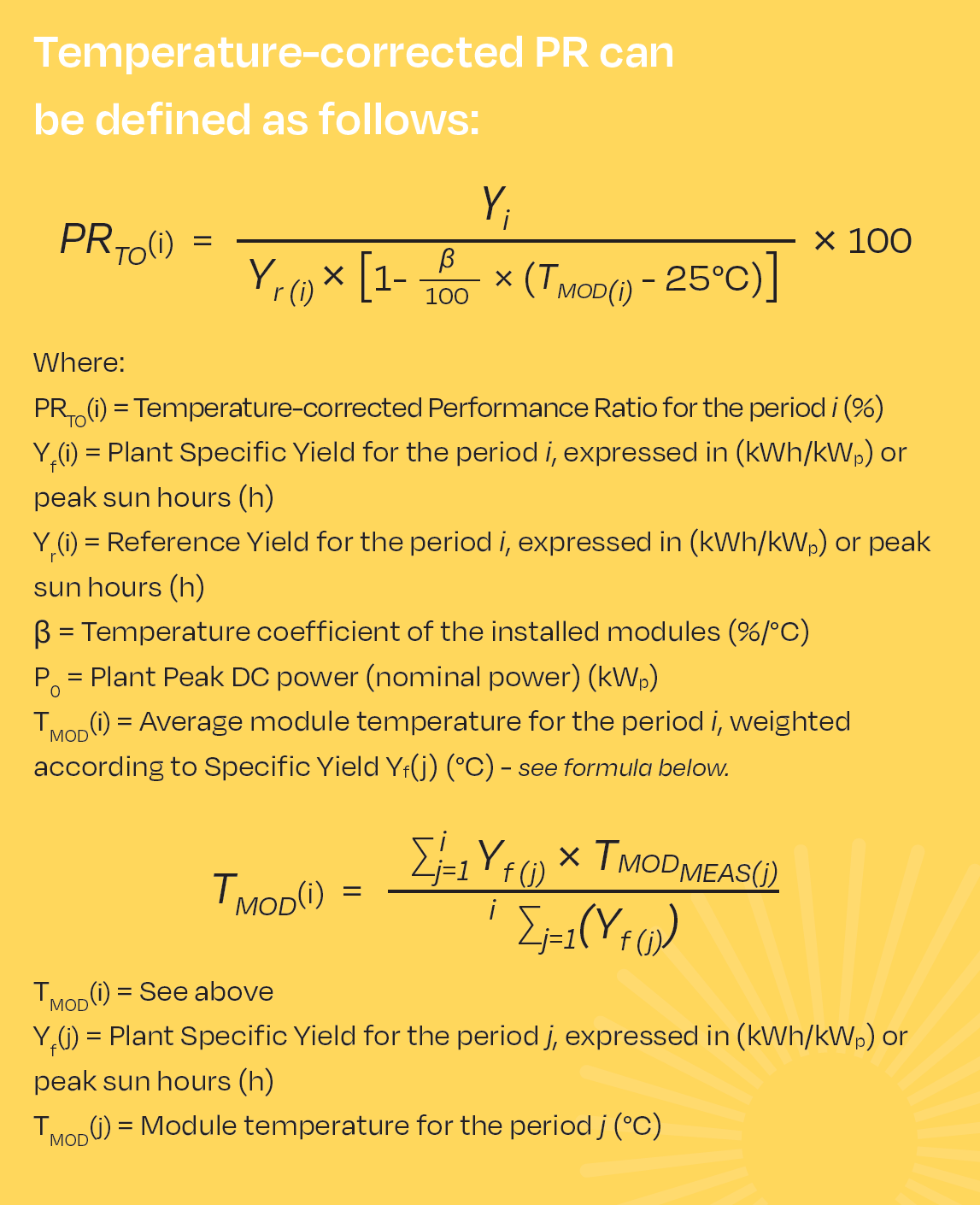

The PR calculations are based on the mathematical definition formula, but each parameter can differ and have its own specifications from contract to contract. It is important to check the consistency of the formula and the input values definitions and measurement rules.

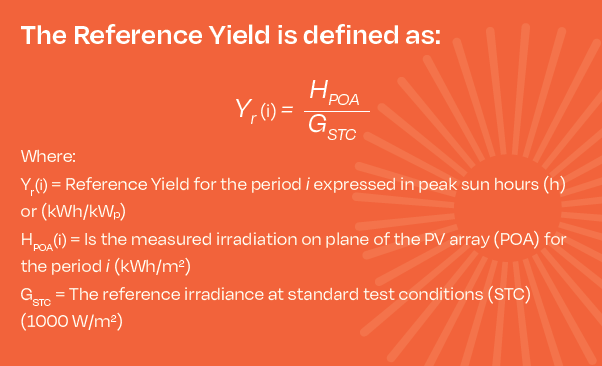

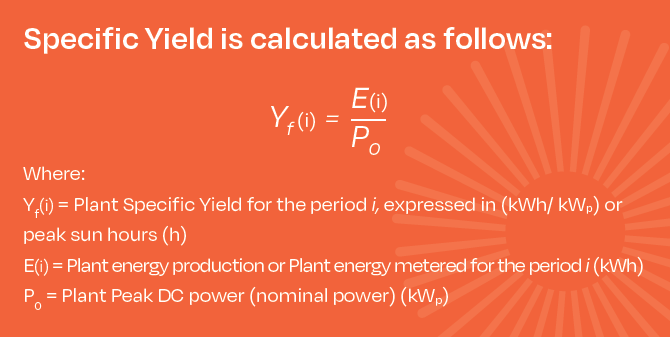

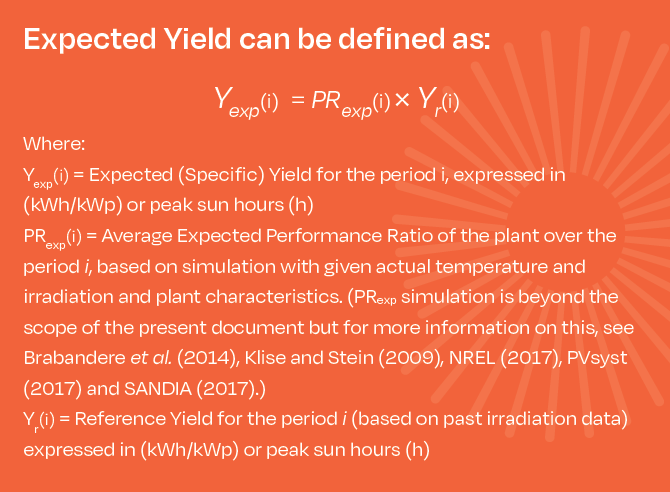

These definitions are based on (Woyte et al. 2014) in line with IEC 61724-1:2017 and are common practice.

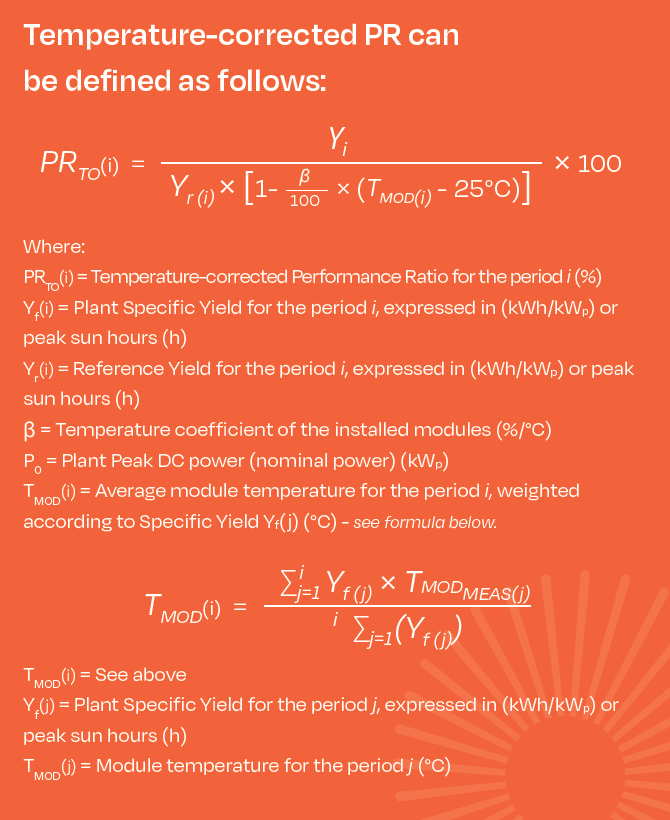

For projects located in regions with high temperatures and temperature variability, a temperature-corrected PR methodology needs to be implemented to account for the weather effects.

Finally, the measured PR is compared to the guaranteed value based on the pre-construction yield assessment simulations. A buffer between the simulated value and the guaranteed one is generally used by the EPC service provider. It is important to ensure that the design reference yield has been updated to reflect any changes made during the project. More specifically, the internal and self-shading factor should be checked for accuracy. The guaranteed PR at Provisional Acceptance should be presented as a monthly breakdown of the yearly simulation to ensure accurate comparison with the measured PR for the testing period. Given the short duration of the test, guaranteed PR at Provisional Acceptance is only used as a validation criterion for the Owner’s “take over”. It does not usually trigger performance liquidated damages as they are linked to the results of annual PR tests. If PR is below the guaranteed threshold, corrective action might be undertaken, and testing should be repeated.

Once the PR criteria and any other requirements have been met, the PAC is issued. The project reaches the handover phase, which is the start of the operational phase and O&M activities.

Other tests

In some contracts, complementary tests can be performed at the Provisional Acceptance stage. These tests can reflect the requirements of the energy off taker with the Power Purchase Agreement (PPA), whether or not the system functions, or simply be used as additional quality assurance measures.

To prove the project’s ability to perform to its maximum capacity, a Reliability Test can be undertaken. This means the project must go a certain period (e.g., 7 consecutive days, or 100 consecutive hours) without significant system failure or malfunction. Furthermore, the project must prove that it can run for a certain amount of time without inverter failures or shutdowns, with full availability of AC and DC equipment, and less than a certain threshold (typically 2%) of string or tracking system failure (if any). If a system failure or malfunction occurs, corrective action shall be taken by the EPC service provider and the Reliability Test is restarted the following day.

Additionally, a Capacity Test may be required to prove that the installed capacity can reach the level promised to the off taker. This is usually based on the DC capacity of the plant, calculated based on the peak powers of the installed PV modules, as stated on the manufacturer’s data sheets. Alternatively, this is calculated from the sum of the peak powers of the Flash Test of the PV modules, provided by the manufacturer at shipment. These values must be signed off by an independent third-party.

Start of plant commercial operation

Once all performance tests described in the above sections have been completed, the Asset Owner issues the PAC and commercial production starts (Commercial Operation Date).

To ensure a smooth and efficient handover to operation activities, the Asset Owner should be involved well in advance and participate in the commissioning phase and performance tests. It is also a best practice to involve the operations function of the Asset Owner during the development and engineering phase, so that an O&M perspective can also be taken into consideration.

Comprehensive and detailed as-built documentations (Annex E of the O&M Best Practice Guidelines), manuals and procedures (Annex C “Documentation set accompanying the solar PV plant” of the O&M Best Practice Guidelines) should be part of the training activities. For more information on the Handover to a specialised O&M service provider, please refer to Chapter 10 onHandover to O&M.

Intermediate and Final Acceptance Certificate

There is a standard duration of 24 months (depending on the EPC contract) between the start of the Taking-Over phase to the Defects Notification Period. The EPC service provider is usually responsible for O&M and rectifying any defects that may be identified during this period. However, this may vary from market to market. During this period, a performance warranty based on a guaranteed PR is still in place and can be reviewed on a yearly basis. Annual PR tests are crucial for checking the PV plant performance, as they do not include seasonal bias. For smaller scale projects, this Defects Notification Period can be reduced to 12 months. It is always recommended to carry out PR verifications for at least one full year.

The calculation methodology is different to Provisional Acceptance and should be based on long-term PR tests. The guaranteed performance ratio should be adjusted to account for module degradation over the first and second years of operations. Should the measured PR be above the expected threshold of guaranteed value, then Intermediate and Final Acceptance certificates are issued accordingly. The Owner can then issue a performance certificate and release the performance warranty bond of the EPC service provider. This performance certificate constitutes the full acceptance of the PV plant by the Owner and the release of the Contractor’s obligations.

The guaranteed PR (and therefore the guaranteed energy) takes into account any event causing non-production due to periods of plant downtime. Owner and EPC service provider may agree, and provide for this in the EPC contract, not considering certain special events. In general, it is reasonable to exclude certain events that are outside the control of the EPC service provider (e.g., vandalism, plant stop imposed by the Transmission System Operator) and Force Majeure events.

The EPC contract shall include provisions on how to deal with cases where actual performance is lower than guaranteed performance. These provisions in general are included in the penalty clause.

Where actual performance is lower than guaranteed performance, EPC service provider shall:

· Make all interventions necessary to ensure that guaranteed process parameters are achieved

· Liquidate both the production lost (difference between actual and theoretical production during the period from PAC to the Final Acceptance Test) and the estimate of the lost production expected for the remaining useful life of the plant.

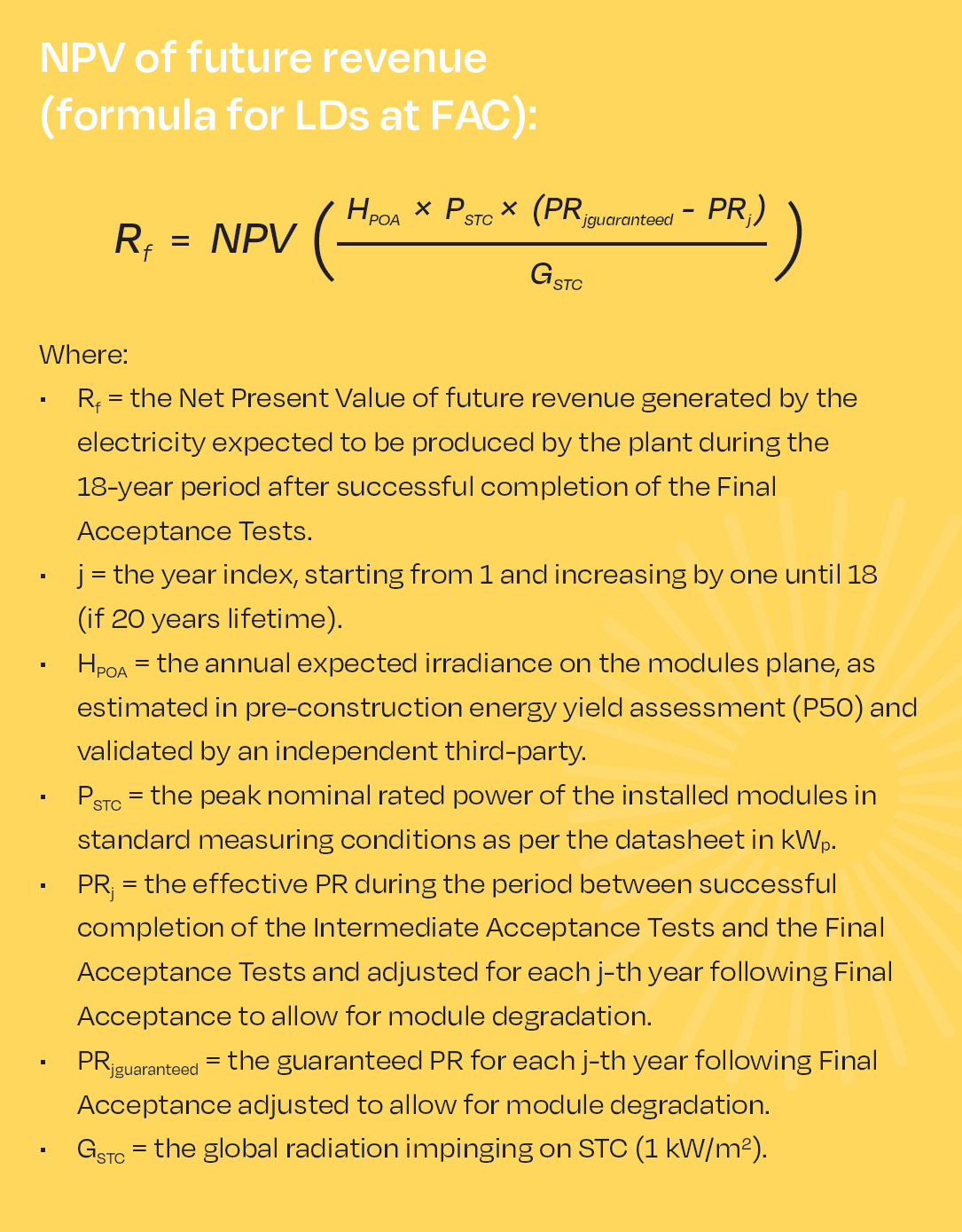

If the measured PR is below the guaranteed levels, the EPC service provider is required to pay performance Liquidates Damages (LDs) up to a certain amount to the Owner for the compensation of revenue losses. During the Intermediate Acceptance phase, the LDs are based on the annual production shortfall and the electricity selling price of the PV plant. During the Final Acceptance phase, the LDs are also calibrated to reflect the loss of revenues that are expected for the full project lifetime or duration of the Power Purchase Agreement. This is usually calculated as the Net Present Value of future revenues shortfall linked to the PR shortfall. Below is an example formula for additional LDs at Final Acceptance:

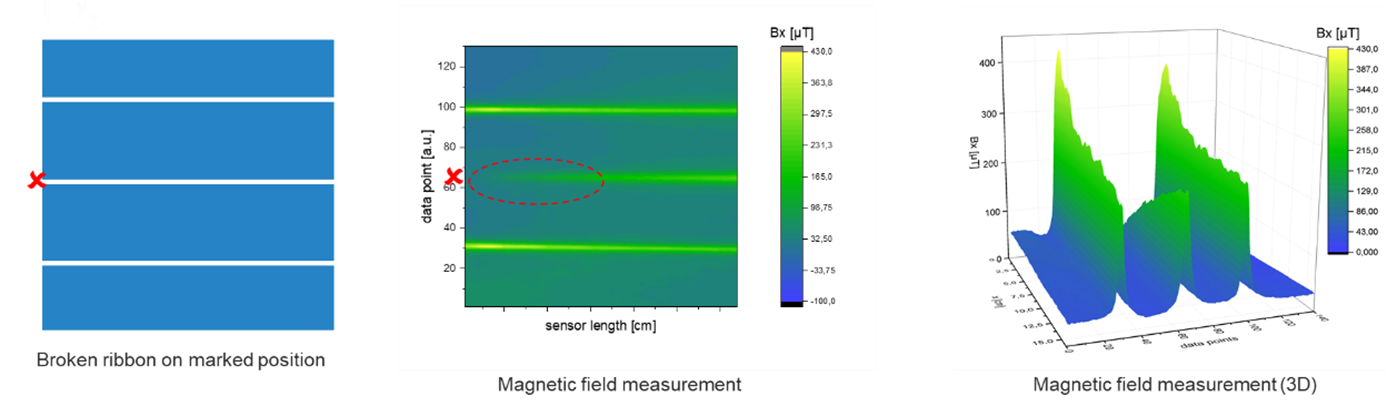

Other requirements at Final Acceptance stage should include an inspection of the whole plant, including the civil works, electrical infrastructure, every piece of equipment and device installed, and the auxiliary systems, to verify that the EPC service provider is leaving the plant in optimum condition. This should ideally be done in the presence of the Owner and an independent third-party (technical advisor). All existing defects must be solved as a condition for acquiring the Final Acceptance Certificate (FAC). Spare parts can also be replenished in accordance with the O&M contract requirements to ensure a smooth transition between both service providers. Additionally, further testing such as repeated module thermography, across all modules, should be performed as a best practice, preferably using aerial inspections during the period between PAC and FAC. This is to ensure that any issues identified can be resolved before the date for Final Acceptance. It will enable the identification of any early-stage degenerative issues. These activities can be included within the EPC service provider’s scope or under the responsibility of the Owner at their own costs.

After the Final Acceptance Test the Owner shall issue the FAC and shall take over the full responsibility of the plant.

Data and communications

Data and Monitoring Requirements

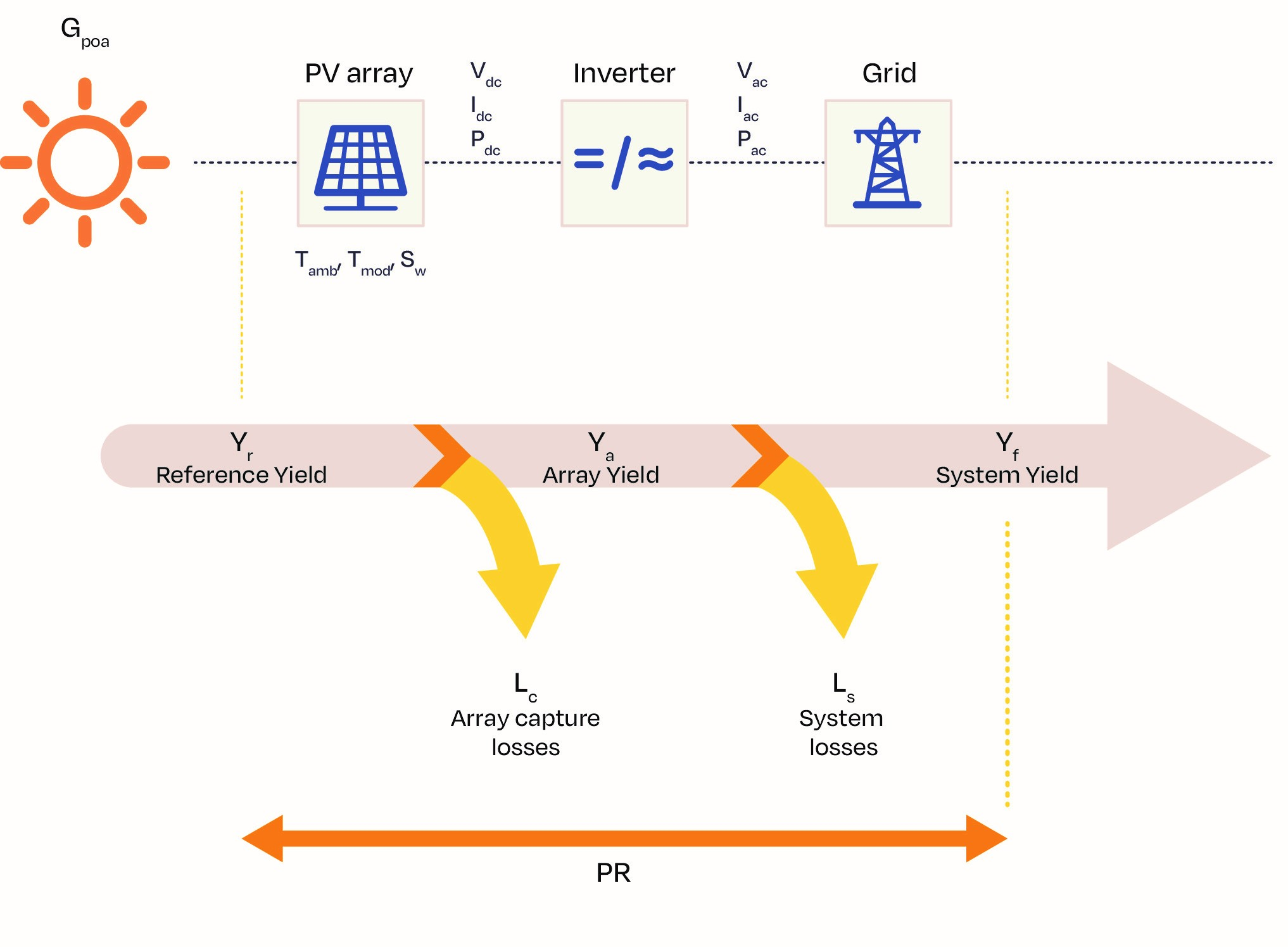

In general, monitoring systems should allow follow-up on the energy flows within a solar PV system. In principle, it reports on the parameters that determine the energy conversion chain. These parameters, along with the most important energy measures in terms of yields and losses, are illustrated in Figure 2. These yields and losses are always normalised to installed solar PV power at standard test conditions in kilowatt-peak (kWp) for ease of performance comparison.

All components and different aspects of technical data management and monitoring platforms are described in the following paragraphs. Reference should also be made to the Monitoring Checklist of the Solar Best Practices Mark for a synthesis of the most important best practices and recommendation with respect to these points.

Data loggers

The main purposes of a datalogger are:

· Collecting data of relevant components (inverters, meteorological data, energy meter, string combiners, status signals) with every device registered separately

· Basic alarm functionality (e.g., Field Communication issues, time critical events like AC Off)

· Providing a temporary data backup (in case of missing internet connection)

· Supporting the technicians during commissioning (e.g., checking whether all inverters work and feed-in)

In addition to this, some dataloggers can also provide the following functions:

· Power Plant Controller (Monitoring & Control should be managed by one instance to avoid communication issues regarding concurrent access). The Power Plant Controller can be integrated in the datalogger or can be a separate device using the communication channel of the datalogger or even a separate one with preferential bandwidth

· Solar Energy Trading Interface (control the active power by a third-party instance like energy trader)

As best practice, dataloggers should be selected following a list of criterion by the operating party as listed below. For example, an EPC service provider will choose and install the data logger used to monitor the site. This datalogger should be selected:

· for its compatibility with the inverters and auxiliary equipment present on site. Preference for inverter-agnostic dataloggers

· for any command functionality that may be needed (this is site type and country specific)

· for its connectivity strength to the internet

· for its robustness (longevity of life and durability for the environmental conditions it will be kept in)

· for its cyber security measures (and those of the cloud server to which it is connected), namely the possibility to set up a VPN tunnel at least

· for its capability to store data during internet communication outages

The recording interval (also called granularity) of the datalogging should range from 1 minute to 15 minutes. Within one monitoring environment granularity should be uniform for all the different data collected.

As a minimum requirement, data loggers should store at least one month of data. Historical data should be backed up constantly by sending it to external servers and, after every communication failure, the data logger should automatically send all pending information. Moreover, data transmission should be secure and encrypted. There should also be a logbook to track configuration changes (especially relevant when acting as Power Plant Controller).

As a best practice, the data logger should store a minimum of three months of data locally and a full data backup in the cloud. Moreover, the operation of the data logger itself should be monitored. This should be done remotely and from an independent server, delivering information on the data loggers’ operating status at Operating System (OS) and hardware level. It should also provide alerts to the Operations room in case of failures and communication loss.

Best practice is to have dataloggers and routers constantly monitored by a watchdog device on-site. In case of no response to the control unit, the power supply will be interrupted by the watchdog unit, performing a hard reset on the stopped equipment. In cases where it is not possible to have an external watchdog it can be useful to have an automatic reboot function.

The entire monitoring installation should be protected by an uninterruptable power supply (UPS). This includes data loggers, network switches, internet modems/routers, measurement devices and signal converters.

Data Quality & Curation

The main purpose of the monitoring system is to collect data from all the relevant components (energy meters, meteorological sensors, inverters, string combiner boxes, etc.) which are typically installed across the field and connected to the plant SCADA through the local network by using various technologies (serial links, cable, fiber, wireless, etc.). Moreover, renewable plants, and solar plants, are often situated in remote environments, and sometimes in harsh places. As such, equipment and systems are subject to difficult conditions and are often subject to data quality issues.

The data quality issues that equipment may face may be categorised as follow:

· False negative values

· Outliers

· Spikes

· Data gaps

· Junk values

These data quality issues can provoke situations that vary extremely depending on the plant, type of measurement, or systems in place. As such, it is very difficult to implement an overall and systematic data quality strategy for renewable Asset Owners as each case is unique.

The data quality issues mentioned above are obvious and may impact many KPIs which are calculated on this basis. More challenging to identify, are slight and progressive data deviations overtime.

Biased KPIs lead to unnecessary operations costs (unrequired on-site intervention) and performances losses, as defects may remain undetected.

As a best practice, the monitoring solution and system should be capable of filtering these values in the most automated and personalised way to cater for each specific case.

Most effective techniques for data validation are based on the analysis of data over relatively long timespans (i.e., daily data validation), with a granularity between 1 and 15 minutes.

Monitoring (web) portal

The main purposes of the monitoring portal are:

· Reading any type of raw data coming from any type of data logger or other solar PV platforms with no preference on brands or models

· Creating a long-term archive for all raw data provided by the asset

· Modelling each solar PV asset using all available information regarding the actual set up and devices (type of devices, installation/replacement date, modules-string-inverter system layout, modules inclination, orientation, type of installation etc.)

· Visualising aggregated data in the highest possible granularity (1 to 15 min is a best practice for most of the indicators)

· Visualising data in standard and specific diagrams

· Computing and visualising dashboards and views of KPIs. For the list of indicators to be computed, see Chapter 10. Indicators computational inputs might be selectable by the user

· Validating data quality (e.g., through calculation of data availability)

· Detecting malfunctions as well as long term degradations with customisable alarms

· Handling alerts from field devices like dataloggers or inverters

· Calculating typical KPIs (such as PR and Availability) with the possibility to adapt parameters

· Providing consistent and easy to use aggregated KPIs for customisable reports for single plants and portfolios

· Making data available via a standardised interface for use in other systems

The monitoring portal should fulfil the following minimum requirements:

· Accessibility level of at least 99% across the year

· Interface and/or apps dedicated to use cases (on-site service, investor etc)

· Customisable user Access Level

· Graphs of irradiation, energy production, performance, and yield

· Downloadable tables with all the registered figures

· Alarms register

As best practice, the following features will also be included in the Monitoring Portal:

· Configurable User Interface to adjust the views depending on the target group (e.g., O&M service provider, EPC service provider, Investor, Asset Manager)

· User configurable alarms

· User configurable reports

· Ticket system to handle alarm messages

· Plant specific KPIs

· Integrate Third Party Data (e.g., solar power forecast, meteorological data, satellite data for irradiance)

· Granularity of data should be adaptable for downloads of figures and tables

The above lists are not exhaustive. For a comprehensive overview of recommended functionalities, refer to the Monitoring Checklist of the Solar Best Practices Mark.

Data format

The data format of the recorded data files must respect standards such as IEC 61724 and must be clearly documented. Data loggers should collect all inverter alarms in accordance with original manufacturer’s format so that all available information is obtained.

Configuration

The configuration of the monitoring systems and data loggers needs to reflect the actual layout of plant details (hardware brand, model, installation details such as orientation, wiring losses, set up date, etc.) to better perform expected performances simulations and obtain consistent insight about a plant’s actual status. If this has not been done during the plant’s construction phase, it should be done at the commissioning phase or when a new O&M service provider takes over (recommissioning of the monitoring system).

During commissioning, each single piece equipment monitored should be checked to make sure it is properly labelled in the Monitoring System. This can be done by temporarily covering insolation sensors or switching off others such as string boxes or inverters.

It is best practice to have a Monitoring System capable of reading and recording all IDs from all sensors and equipment it monitors. This will reduce the possibility of mislabelling elements and improve the tracing of equipment and sensor replacement during the life of the facility. Some Monitoring Systems have even an auto-configuration feature (plug-and-play) that reduces start-up time and potential mistakes. This it is done by automatically capturing device IDs and configuration information. This also allows for automatic detection of inverter or sensor replacement.

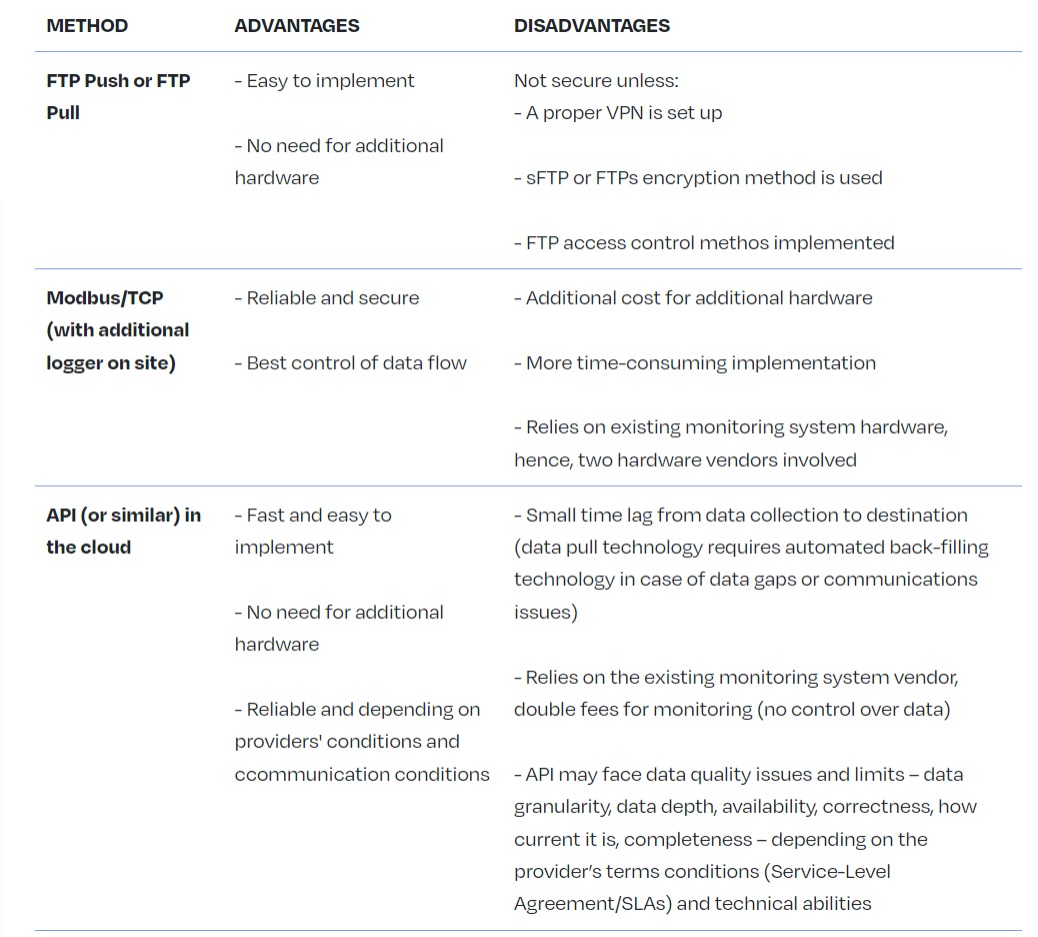

Interoperability

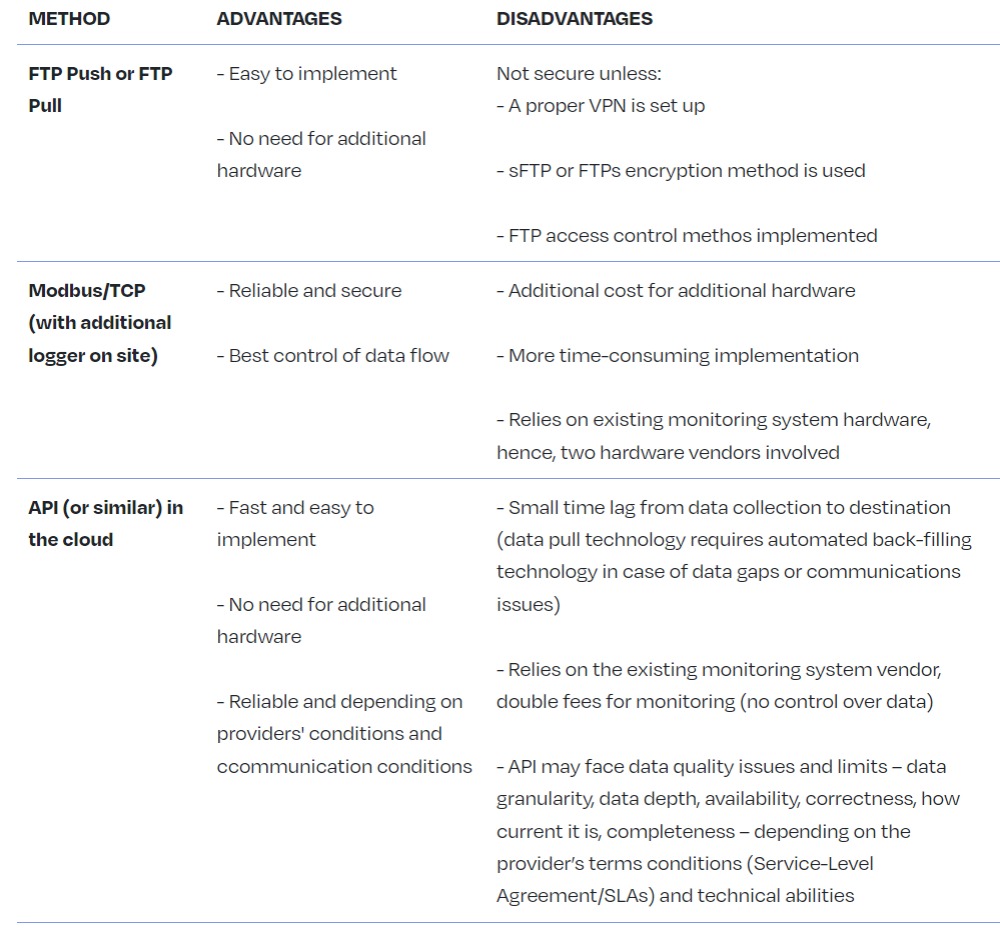

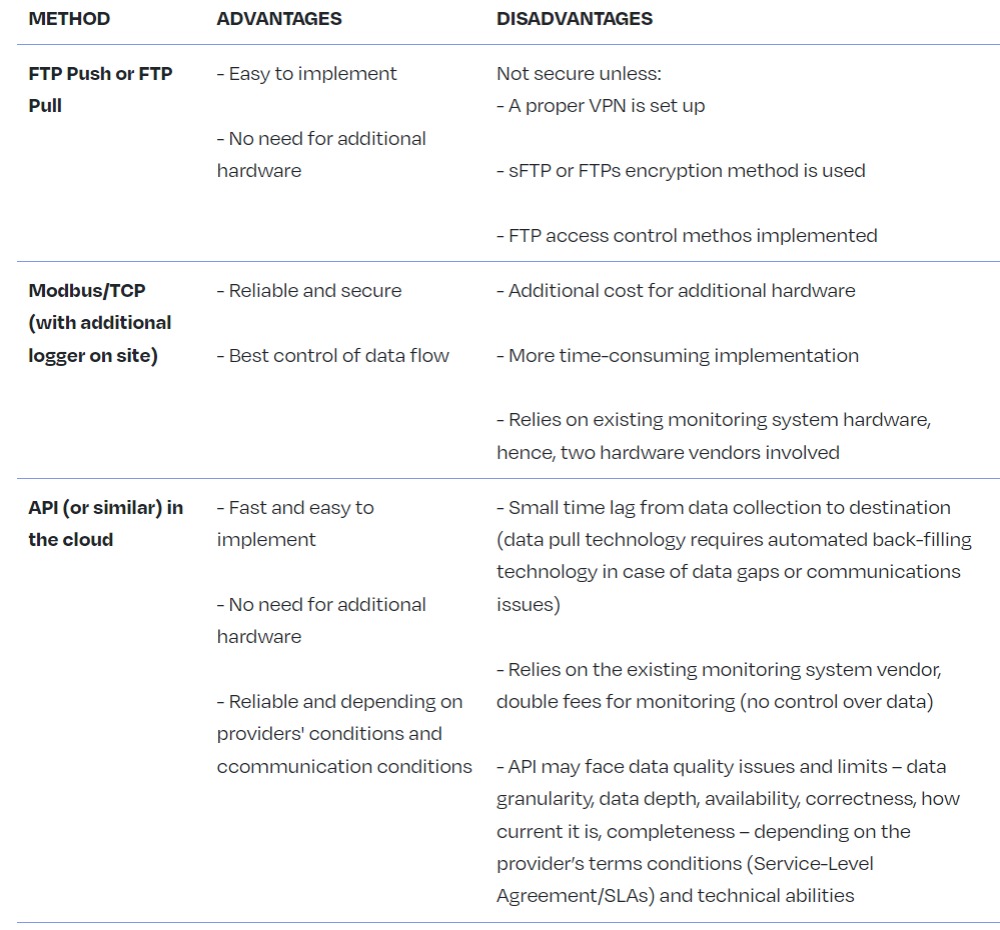

As a best practice, the system should ensure open data accessibility (both for sending and receiving data bilaterally) to enable easy transition and communication between monitoring platforms. Table 5 shows some examples of data integration options. Due to the lack of unifying standards, every Monitoring System provider has their own method of storing and retrieving data. The best systems can retrieve data by using open interfaces such as RESTful, providing interoperability between different systems.

Another important aspect of interoperability is the ability to aggregate data from different platforms that serve a range of areas in the solar PV business, such as administration, accountancy, planning & on-site intervention, and stock management applications. This way, information can be exploited by the central monitoring platform without affecting the external applications. For example, an O&M service provider works with several types of ticketing systems for different clients. The monitoring platform should be able to collect data from all of them. Likewise, information about tickets managed from the central monitoring system should be automatically transferable to the dedicated ticketing application.

Internet connection and Local Area Network

The O&M service provider should make sure to provide the best possible network connectivity. As a minimum requirement, the bandwidth needs to be adequate enough to transfer data in a regular way.

Whenever a fibre connection is available within the solar PV-site area, this should be used to connect to the internet, with industrial routers considered as standard. Where a fibre connection is unavailable, 4G or Wi-Fi communication is preferred. Satellite connection is the least preferred communication type. An additional back-up system is best practice. Any subscription should allow for the data quantity required and should foresee the amount (e.g., Closed-Circuit Television (CCTV) or not)granularity of the data.

For solar PV power plants larger than 1MW it is advised to have a WAN connection and as an alternative to an industrial router, that allows for mobile or satellite communication back-up in case the WAN connection fails. A system with a reset capability in case of loss of internet connection is recommended. A direct connection to a monitoring server with an SLA guarantees continuous data access. If data passes via alternative monitoring servers without an SLA, (e.g., monitoring portal of the inverter manufacturer), the SLA can no longer be guaranteed. The automatic firmware updates of the data logger should be disabled. Firmware updates are subject to a change management procedure with the monitoring service.

All communication cables must be shielded. Physical distances between (DC or AC) power cables and communication cables should be ensured, and communication cables should be shielded from direct sunlight. Furthermore, cables with different polarities must be clearly distinguishable (label or colour) for avoiding polarity connection errors.

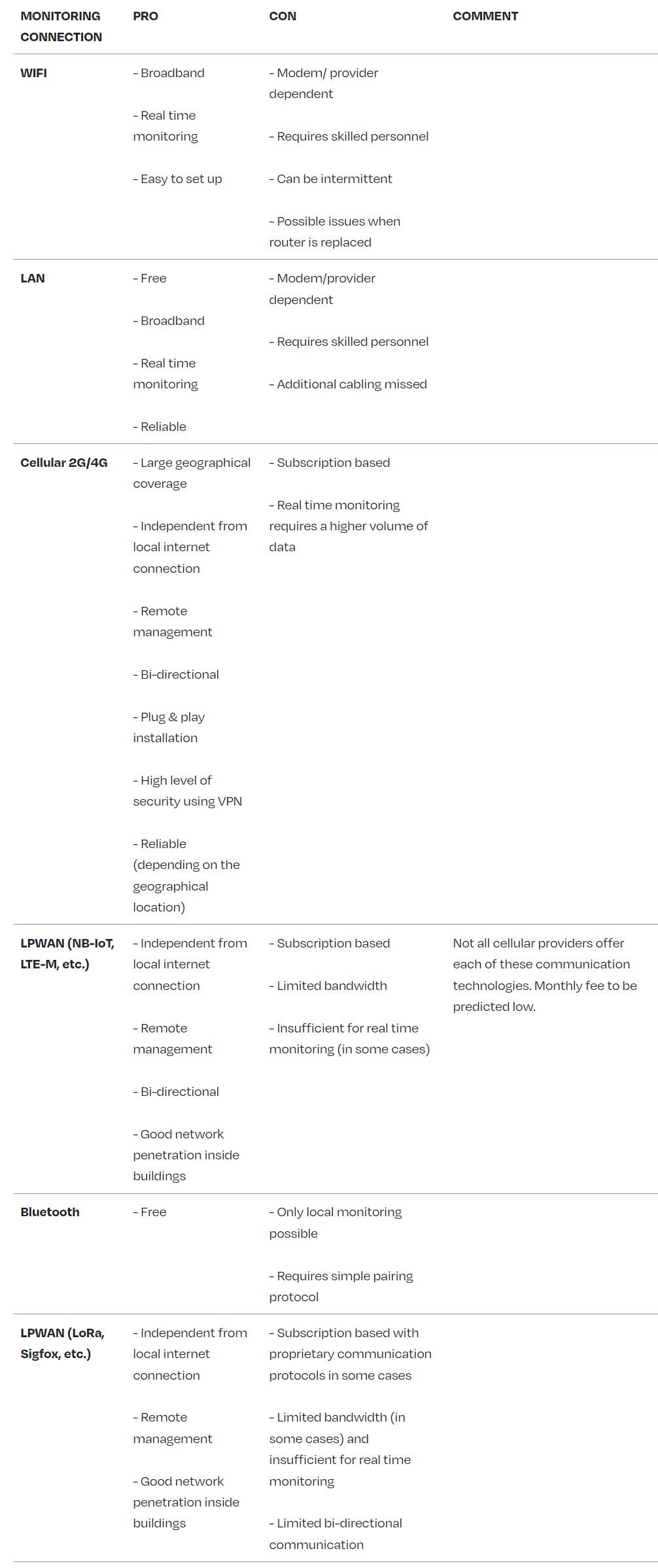

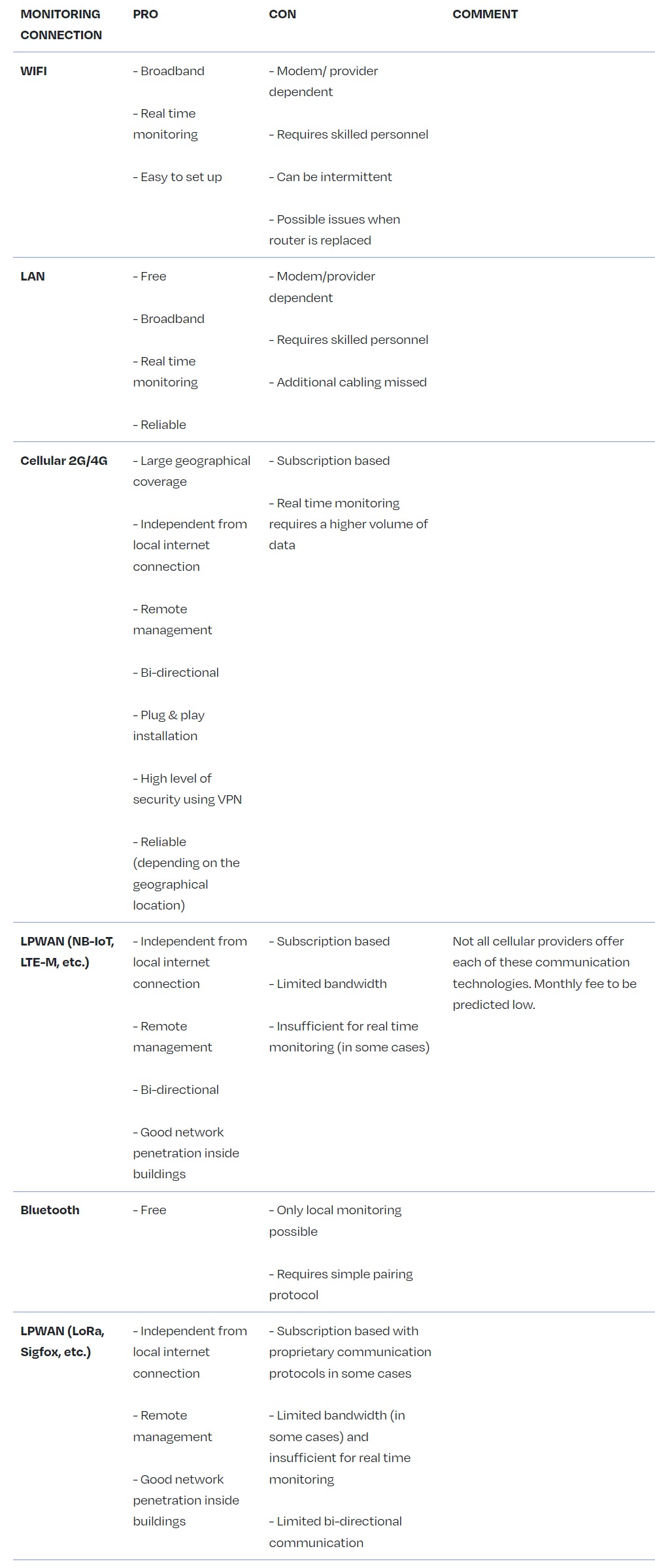

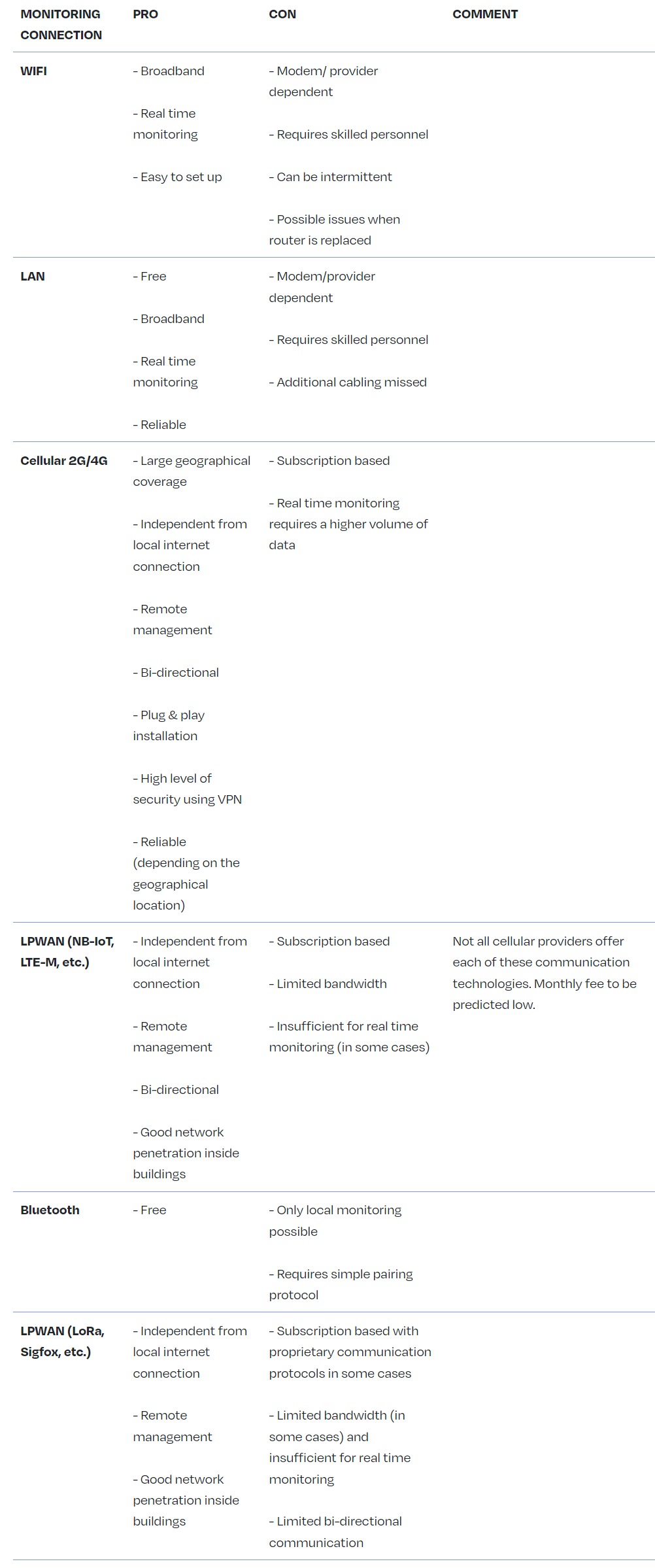

Pros and cons of different types of monitoring connections:

Data ownership and privacy

The data from the monitoring system and data loggers, even if hosted in the cloud, should always be owned by and accessible to the Asset Owner (or SPV). Stakeholders such as the O&M service provider and the Asset Manager need the data to perform their duties and should be granted access. In addition to this, auditors working in the due diligence phases of a project should also have access. It is important to have at least two access levels (read-only, full access).

The monitoring system hardware can be provided by the O&M service provider or a third-party monitoring service provider (but the monitoring system hardware remains the property of the Asset Owner as part of the installation):

· If the O&M service provider is the monitoring service provider, they have full responsibility for protecting and maintaining the data, and ensuring the proper functioning of the monitoring system.

· Where there is a third-party monitoring service provider, responsibility for protecting and maintaining the data resides with them. The O&M service provider should endeavours to make sure performance monitoring is correct and takes the best practices mentioned in the previous paragraphs into consideration. The O&M service provider’s ability to properly maintain and use the monitoring system should be evaluated. If necessary, the O&M service provider should be appropriately trained to use the monitoring system. Data use by third-party monitoring providers should be extremely limited, i.e., for correcting bugs and developing additional functions to their systems.

Cybersecurity

As solar PV power plants have inverters and power plant controllers (and monitoring systems) that are connected to the internet to enable surveillance and remote instructions by operators, there are significant cybersecurity risks.

Cybersecurity comprises technologies, processes and controls that are designed to protect systems, networks, and data from cyber-attacks. Effective cyber security reduces the risk of cyber-attacks and protects organisations and individuals from the unauthorised exploitation of systems, networks, and technologies.

Cybersecurity is a vast area and multiple measures are possible. The following hints may help as a starting point:

· Keep it simple: If possible, reduce the type of network devices to a minimum

· As a recommendation, traffic of the network devices may be monitored to detect abnormally high use of bandwidth

· Secure physical access to the network devices and implement a secure password policy. Avoid the use of standard passwords and change all factory setting passwords

· Control access from Internet via strict firewall rules:

- Port forwarding should not be used because this is a big security gap. Only router ports that are necessary should be opened

- Reduce remote access to the necessary use cases

- The use of VPNs (Virtual Private Networks – a secure connection built up from the inside of the private network) is necessary

- VPN access to the site from outside is a minimum requirement

- A VPN server or VPN service which works without requiring a public IP on-site is preferred

- Each solar PV power plant should have different passwords

- Keep your documentation up to date to be sure that no device has been forgotten

- Use different roles to the extent possible (e.g., read only user, administration access)

- Use professional (industrial grade) hardware; only this hardware provides the security and administration functions your plant needs to be secure

· Implement vulnerability management (i.e., identifying and fixing or mitigating vulnerabilities, especially in software and firmware):

- Improve insecure software configurations

- The firmware and software of devices should be kept up to date

- Use anti-virus software if possible and keep it up to date

- Avoid wireless access if it is not necessary

- Audit your network with the help of external experts (penetration tests)

· Keep your company safe:

- Do not store passwords in plain text format, use password manager (e.g., 1Password, Keepass, etc.)

- Train your employees on IT security awareness

- Do not share access from all plants to all employees. Give access only to those who need it. This way damage can be limited if an individual employee is hacked

- Management of leaving and moving employees; change passwords of plants which are overseen by an employee who has left the company or moved to another department

It is therefore best practice that installations undertake a cyber security analysis, starting from a risk assessment (including analysis at the level of the system architecture) and implement a cybersecurity management system (CSMS) that incorporates a plan-do-check-act cycle. The CSMS should start from a cybersecurity policy, and definition of formal cybersecurity roles and responsibilities, and proceed to map this onto the system architecture in terms of detailed countermeasures applied at identified points (e.g., via analysis of the system in terms of zones and conduits). These will include the use of technical countermeasures such as firewalls, encrypted interfaces, authorisation and access controls, and audit/detection tools. They will also include physical and procedural controls, for example, to restrict access to system components and to maintain awareness of new vulnerabilities affecting the system components.

As a minimum requirement, data loggers should not be accessible directly from the internet or should at least be protected via a firewall. Secure and restricted connection to data servers is also important.

The manufacturer of the datalogger and the monitoring platform should provide information on penetration tests for their servers, any command protocol activation channels, and the results of security audits for their products. Command functions should be sent using a secure VPN connection to the control device (best practice). Double authentication would be an even more secure option.

For further information, beyond the scope of this document, please look at the EU Cybersecurity Act (EC, 2019) and the European Parliament’s study “Cyber Security Strategy for the Energy Sector” (EP, 2016).

Types of data collected through the monitoring system

Irradiance measurements

Irradiance Sensors

Solar irradiance in the plane of the solar PV array (POA) is measured on-site by at least one irradiance Class A quality measurement device and ISO 9060:2018 (ISO 9060 2018). The higher the quality of the pyranometer, the lower the uncertainty will be. Best practice is to apply at least two pyranometers in the plane of the solar PV array. In case of different array orientations within the plant, at least one pyranometer is required for each orientation. It should be ensured that the pyranometers are properly assigned to the different arrays for the calculation of PR and Expected Yield.

Class A Pyranometers are preferred over silicon reference cells because they allow a direct comparison between the measured performance of the solar PV power plant and the performance figures estimated in the energy yield assessment. For plants in Central and Western Europe, measuring irradiance with silicon cells yields approximately 2 to 4% higher long-term PR than with a thermopile pyranometer (N. Reich et al. 2012).

Irradiance sensors must be placed in the least shaded location. They must be mounted and wired in accordance with manufacturers’ guidelines. Preventive Maintenance and calibration of the sensors must follow the manufacturers’ guidelines.

The irradiance should be recorded with a granularity of up to 15 minutes (minimum requirement).

Further information on the categorisation of plant sizes and the use of appropriate measuring technology is provided in IEC 61724-1.

Satellite-based Irradiance Measurements

In addition to irradiance sensors, complementary irradiance data from a high-quality satellite-based data service can be acquired after a certain period to perform comparisons with data from ground-based sensors. This is especially useful in case of data loss or when there is low confidence in the data measured onsite by the Monitoring System and it can be considered as best practice. In particular, high-quality satellite-based data should be used for irradiation sensor data quality assessments. The longer the period considered the lower the error will be for satellite-based irradiation data. For daily irradiation values, the error is relatively high, with root-mean-square error (RMSE) values of 8 to 14% in Western Europe. For monthly and annual values, it decreases below 5 and 3%, respectively, which is in line with an on-site sensor (Richter et al. 2015).

When satellite-based irradiance data is used, hourly granularity or less (15 minutes if possible) is recommended. The data must be retrieved once per day at least.

Module temperature measurements

Module temperature can be measured for performance analysis in KPIs such as the temperature-corrected PR.

The accuracy of the temperature sensor, including signal conditioning and acquisition done by the monitoring system hardware, should be < ±1 °C.

The temperature sensor should be attached to the middle of the backside of the module in the middle of the array table, in the centre of a cell, away from the junction box with appropriate and stable thermally conductive glue (Woyte et al. 2013). The installation should be in accordance with manufacturer guidelines (e.g., respecting cabling instructions towards the data logger).

Varying solar PV module temperature in a plant is mainly due to different wind exposure. Therefore, in large plants more sensors will be required across the site because module temperature should be measured at different representative positions (e.g., for modules in the centre of the plant and for modules at edge locations where temperature variation is expected).

The granularity of module temperature data should be at least 15 minutes to perform a correct PR calculation.

Local meteorological data

It is best practice to measure ambient temperature, wind speed, rain fall and other site relevant meteorological measurement with the installation of a local meteorological station in accordance with the manufacturers’ guidelines. Ambient temperature is measured with a shielded thermometer, such as a PT100. The shield protects the sensor from radiative heat transfer. Wind speed is measured with an anemometer, at 10m above ground level.